Introduction

Invented in 2017 and first presented in the ground-breaking paper “Attention is All You Need”(Vaswani et al. 2017), the transformer model has been a revolutionary contribution to deep learning and arguably, to computer science as a whole. Born as a tool for neural machine translation, it has proven to be far-reaching, extending its applicability beyond Natural Language Processing (NLP) and cementing its position as a versatile and general-purpose neural network architecture.

In this comprehensive guide, we will dissect the transformer model to its core, thoroughly exploring every key component from its attention mechanism to its encoder-decoder structure. Not stopping at the foundational level, we will traverse the landscape of large language models that leverage the power of the transformer, delving into their unique design attributes and functionalities. Further expanding the horizons, we will explore the applications of transformer models beyond NLP and probe into the current challenges and potential future directions of this influential architecture. Additionally, a curated list of open-source implementations and supplementary resources will be provided for those intrigued to explore further.

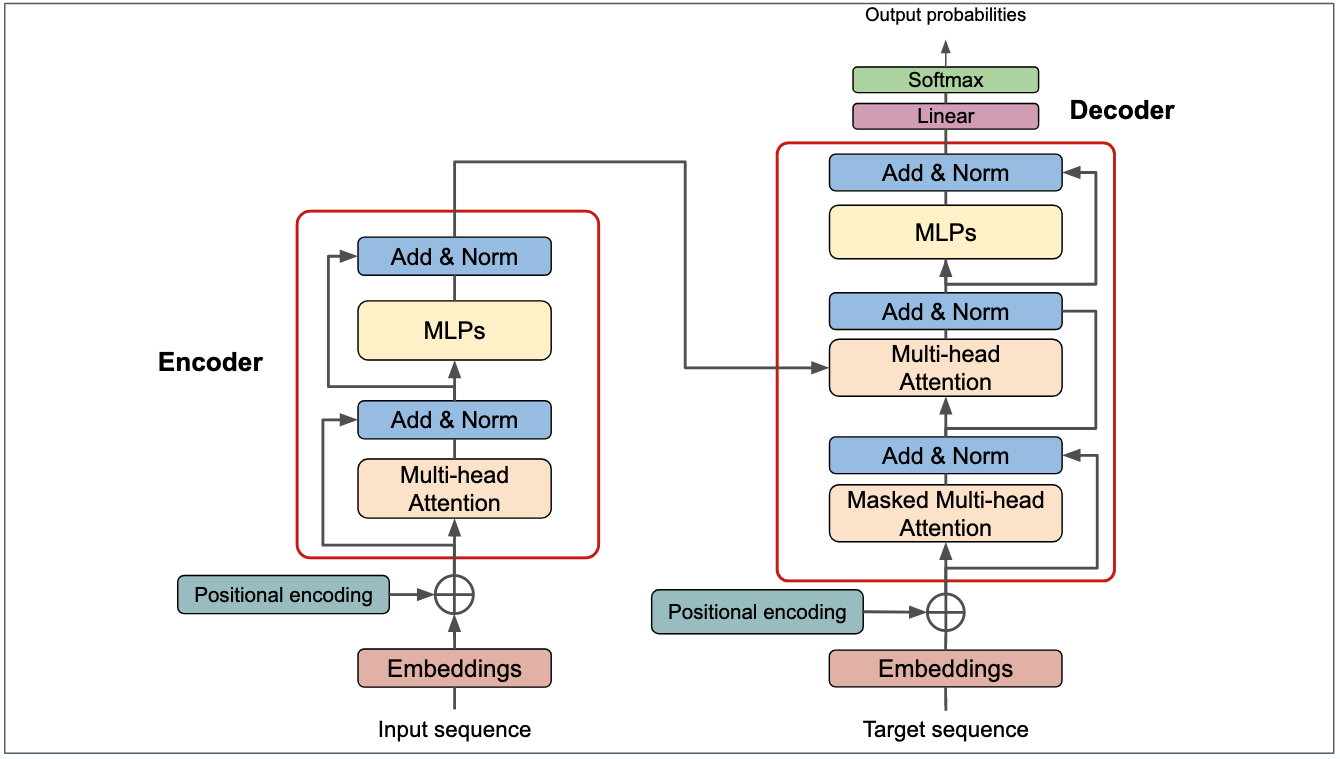

Fig 0: Transformer Architecture that we will explore in depth in this article. Adapted from Vaswani et al. 2017.

Fig 0: Transformer Architecture that we will explore in depth in this article. Adapted from Vaswani et al. 2017.

Neural Networks Before Transformers

The designers of transformer neural architecture were interested in finding an architecture that could work for sequence to sequence modelling. It wasn’t that there weren’t existing sequence modelling architectures, it’s just that they had many drawbacks. What are other kinds of neural networks that be used for sequence modelling? What are their drawbacks? Let’s seek the answers to those questions as we motivate transformers along the way.

MultiLayer Perceptrons(MLPs)

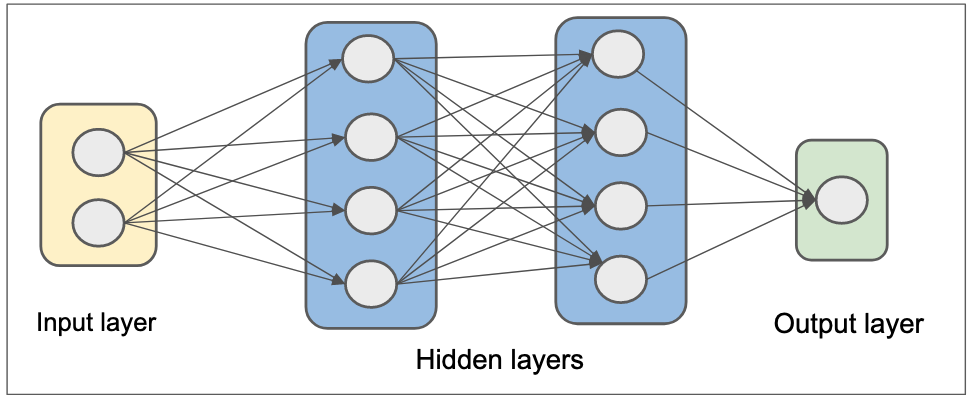

Let’s start with multilayer perceptrons(MLPs), one of the classical neural network approaches. MLPs are not super powerful themselves but you will find them integrated in almost any other architecture(surprisingly even in transformer). MLPs are basically a sequence of linear layers or fully connected layers.

Fig 1: Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs)

Fig 1: Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs)

MLPs have long been used to model different kinds of data way before the AI community find best architectures for various modalities but one thing for sure, they are not suitable for sequence modelling. Due to their feedforward design, they can not preserve the order of information in a sequence. Sequence data lose meaning when the order of the data is lost. Thus, the inability of MLPs to preserve order of information make them unsuitable for sequence modelling. Also, MLPs takes lots of paramaters which is another undesired property a neural network can have.

Convolutional Neural networks

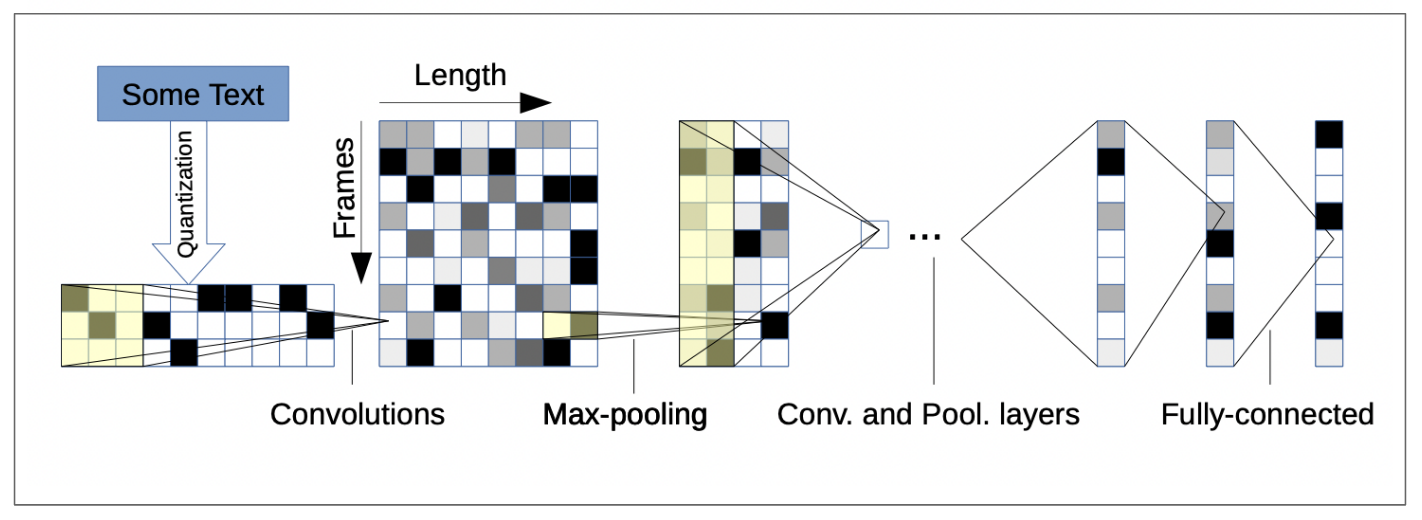

Convolutional neural networks(CNNs or ConvNets) are a class of neural network architectures that are most known for processing images and other modalities such as texts and videos.

Fig 2: Convolutional neural networks for text understanding. Adapted from X. Zhang and LeCun 2015.

Fig 2: Convolutional neural networks for text understanding. Adapted from X. Zhang and LeCun 2015.

ConvNets have so far been successful in small scale and large scale visual recognition but not quite successful in sequence modelling. They are easy to parallize(good for GPUs), due to their locality(computations are bundled in local parts of the input data), they require many layers to handle long-term dependencies. As opposed to images that have fixed length, most sequential data have variable length, something that neither ConvNets or MLPs can handle.

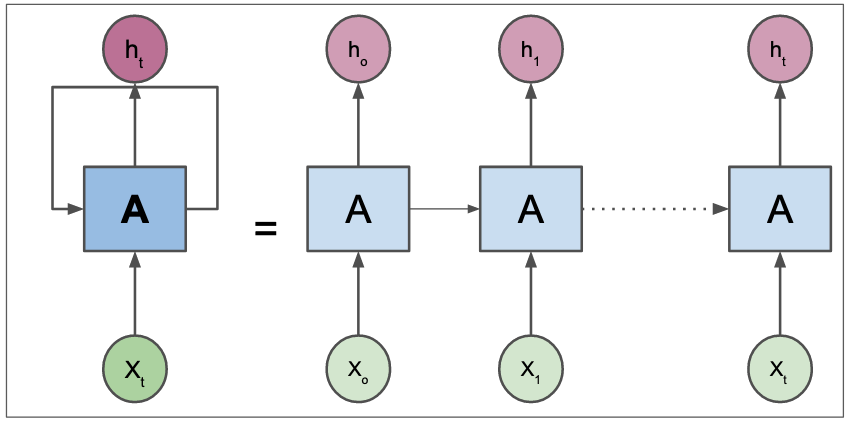

Recurrent Neural Networks

Unlike MLPs or ConvNets, recurrent neural networks(RNNs) were designed with sequence in mind. RNNs have feedback loop in their design, a key element in their ability to model sequential data. Another desirable property of RNNs is that they can handle variable length data.

There are fundamental problems in how RNNs are wired. Firstly, due to their sequential design, they are likely to be unstable for long-term sequences. Secondly, they can not parallized which limit their scalability on modern machine learning accelerators(like GPUs).

Fig 3: Recurrent neural networks (RNNs).

Fig 3: Recurrent neural networks (RNNs).

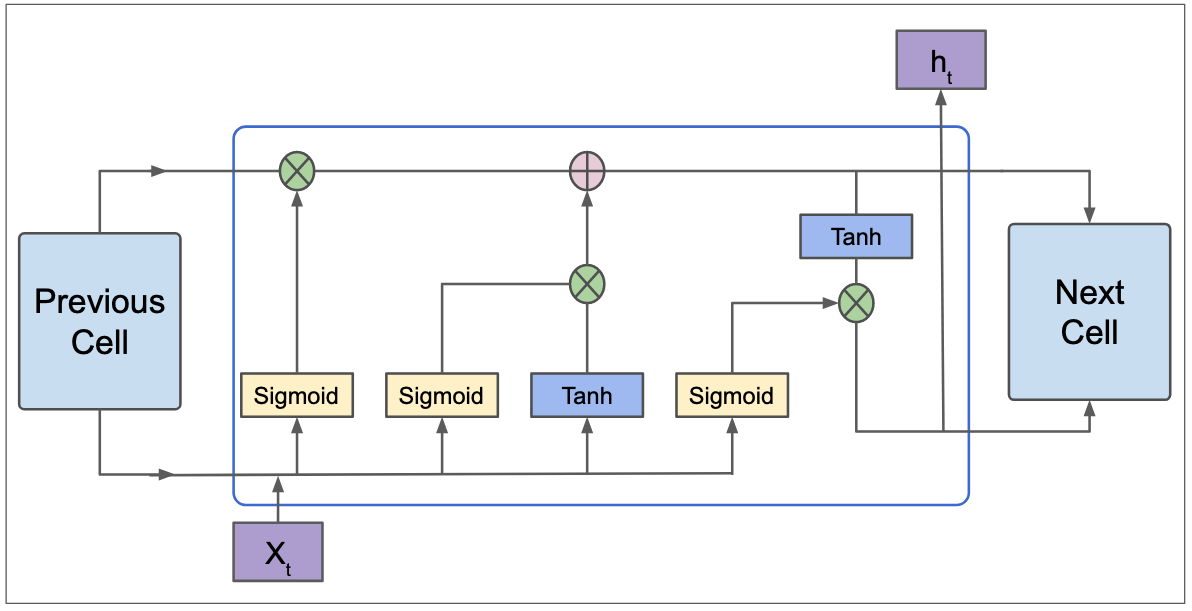

Recurrent networks have many variations. One of their famous version is Long Short Term Memories(LSTMs). LSTMs can handle long-term sequences. They have a cellstate(horizontal straight line in figure below) and gates which all smooth the flow of information.

Fig 4: Long Short Term Memories (LSTMs).

Fig 4: Long Short Term Memories (LSTMs).

Another slightly efficient version of LSTMs is gate recurrent Units(GRUs). LSTMs works great for basic sequence modelling problems but they are still limited in how far they can go. As we previously said, they can not parallized which means they can not be scaled. Also, even if they can preserve the order of information, they can not reason about the global context of the data they are processing. Context is important. Take an example in machine translation(the task that basically gave us transformer), context of sentence being translated is as important as the order.

All we have been doing basically is to motivate the transformers. So far, we have seen that prior neural networks were either not suitable for sequence modelling or not parallizable or not stable or limited in context length, all of which are primary desirable traits of sequence neural architectures.

Now that we have the right background, let’s dive into transformer architecture.

Transformer Architecture

Transformer is a neural network architecture that can process sequential data such as texts, audios, videos, and images(as a sequence of image patches). Transformer does not use any recurrent or convolution layers. It’s fundamental layer is called Attention. It also contain other basic layers such as fully-connected layers, normalization layer(LayerNorm mostly)(Ba, Kiros, and Hinton 2016), embedding layer, and positional encoding layer. We will see what each of those layers performs in next sections.

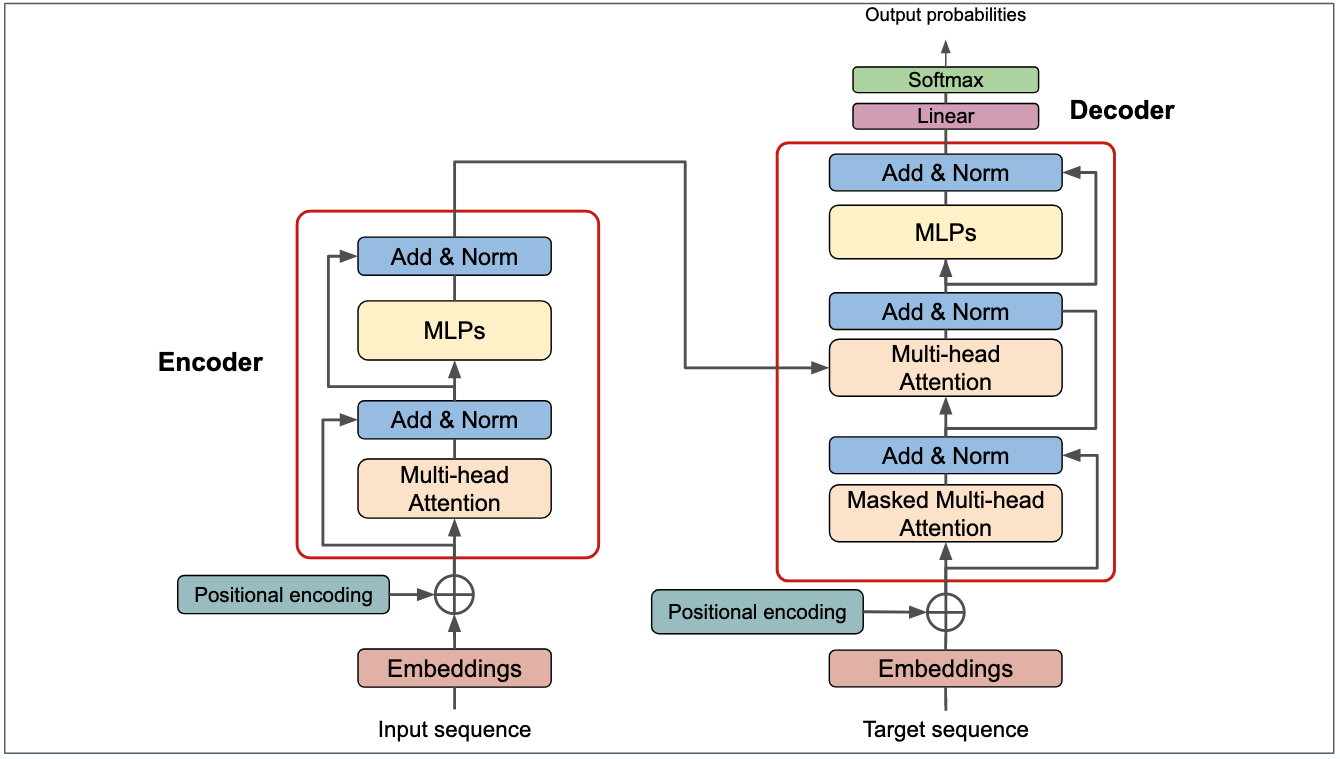

Fig 5: Transformer Architecture. Adapted from Vaswani et al. 2017.

Fig 5: Transformer Architecture. Adapted from Vaswani et al. 2017.

As we alluded to in the beginning, transformer was initially introduced for machine translation, a task that demands processing two sequences(both input and output are sequences). Thus, the transformer model had two parts: encoder for processing the input and decoder for generating the output. More about encoder, decoder, and other layers are discussed below.

Encoder

Encoder is one of the main blocks of the transformer architecture that is right at the input of input sequence. Encoder transforms input sequence into compressed representation. In the orginal transformer architecture, the encoder was repeated 6 times(this depends on overall size of architecture, it can be changed). Each encoder block has 3 main layers which are multi-head attention(MHA), layer norm, and MLPs(or feedforward according to the paper).

Multi-head attention and MLPs are referred to as sub-layers in the transformer paper. Between sublayers, there are layer normalization and dropout and residual connections in between(refer to diagram for correct flow of those layers).

The number of encoder layers was 6 as said previously. The more the number of encoder layers, the larger the model, and the more the model is likely to capture the global context of the input sequences hence resulting in better task generalization.

Decoder

The decoder is pretty much the same as encoder except additional multi-head attention that operated over the output of the encoder. The goal of the decoder is to fuse encoder output with the target sequence and to make predictions(or to predict the next token).

The attention that takes the target sequence in decoder is masked to prevent the current token(being processed) from attending to subsquent tokens in the target sequence. If the decoder has access to a full target sequence, this would basically be cheating and can result in model that can not generalize beyond the training data.

Decoder is also typically repeated the same times as encoder. In the orginal transformer, the number of decoder blocks were also 6 blocks.

Attention

What Really is Attention?

Attention is the principal element of transformer architecture. In essence, attention is a mechanism that can allow the neural network to pay more attention to the part of input data that contains meaningful information and pay less attention to the rest of the input.

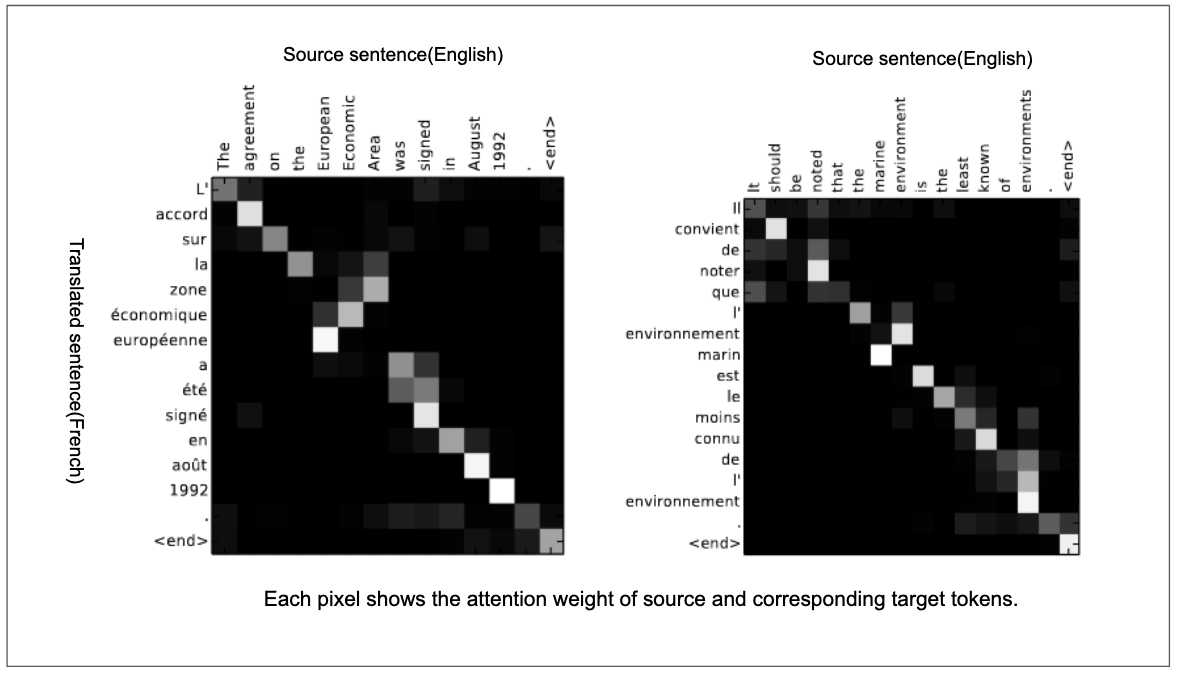

The attention mechanism was used in various tasks long before the introduction of transformer architecture. The idea of attention first appeared in neural machine translation(NMT) approach that used attention to find the set of positions in input sentence where the most relevant information is concentrated(Bahdanau, Cho, and Bengio 2014). Because their attention based NMT could align and translate jointly or simultaneously, it surprisingly performed well than previous approaches. As you can see in the image below, the network was able to find the correct order of words in a translated sentence, a feat that prior neural machine translation approaches struggled to achieve.

Fig 6: Aligning the source sentence and target sentence in neural machine learning translation. Adapted from Bahdanau, Cho, and Bengio 2014. The x-axis and y-axis show the source sentence and translated sentence, respectively. Each pixel indicates the attention weights of the source (input) token with its corresponding target token. The diagonal attention represents words that are in corresponding order (e.g., the agreement on the -> L’accord sur la). Attention can figure out the correct word order (e.g., European Economic Area -> zone économique européenne).

Fig 6: Aligning the source sentence and target sentence in neural machine learning translation. Adapted from Bahdanau, Cho, and Bengio 2014. The x-axis and y-axis show the source sentence and translated sentence, respectively. Each pixel indicates the attention weights of the source (input) token with its corresponding target token. The diagonal attention represents words that are in corresponding order (e.g., the agreement on the -> L’accord sur la). Attention can figure out the correct word order (e.g., European Economic Area -> zone économique européenne).

What’s going on in the image above? Can you spot something? The order of words was reversed in translated sentence wherever it make sense in target language. Thus, when translating a sentence, attention can give the model the ability to not only translate the sentence correctly, but to also translate it in the right order based on the context of the target language. In brief, attention can identify and preserve the context when translating one language to another.

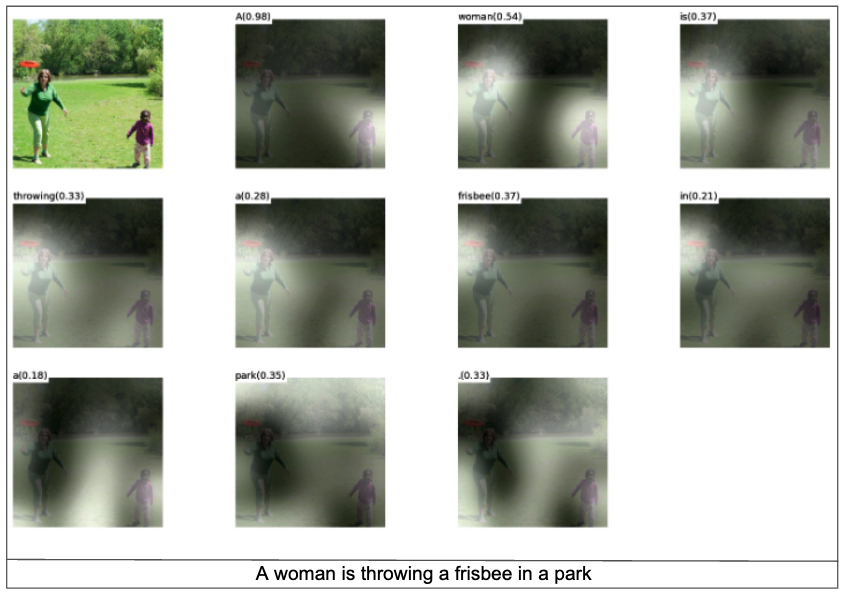

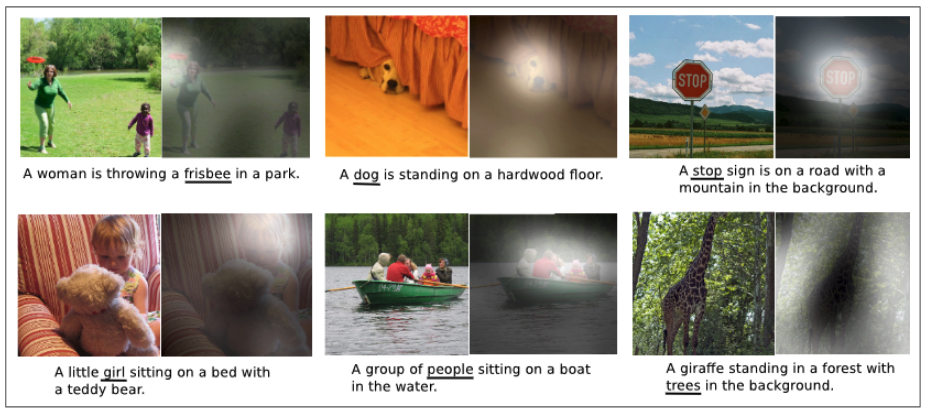

Another earlier work that used attention is found in neural image captioning(Xu et al. 2015). In this work, the authors used ConvNets for features extraction and RNNs with attention mechanism to generate a caption that aligns best with the input image. The image belows(taken from the paper) shows where the model roughly attends to.

Fig 7: Generating caption with neural captioning model. The white regions show where the model is focusing when generating the caption “A woman is throwing a frisbee in a park”. Image from Xu et al. 2015.

Fig 7: Generating caption with neural captioning model. The white regions show where the model is focusing when generating the caption “A woman is throwing a frisbee in a park”. Image from Xu et al. 2015.

On a global level, integrating attention mechanism in image captioning model helps the model to attend to the meaningful part of the input image when generating a caption.

Fig 8: The model can attend to key objects when generating captions. Image taken from Xu et al. 2015.

Fig 8: The model can attend to key objects when generating captions. Image taken from Xu et al. 2015.

Both the examples we used above demonstrate the effectiveness of attention. Attention is really a magic mechanism that allows the neural network to focus on part of input data that contains meaningful information and focus less on rest of the input data.

Now that we understand attention, let’s look at the inputs of attention function in transformer architecture: querry, keys, and values.

Attention Function: Query, Key, Value

Intuitively, attention is really “focus on most important part of the input data”. Technically speaking, attention measures the similarity between two vectors and return the weighted similarity scores. A standard attention function takes three main inputs which are query, key, and value vectors. Before breaking down the attention function, let’s try to understand what keys, values, and queries mean.

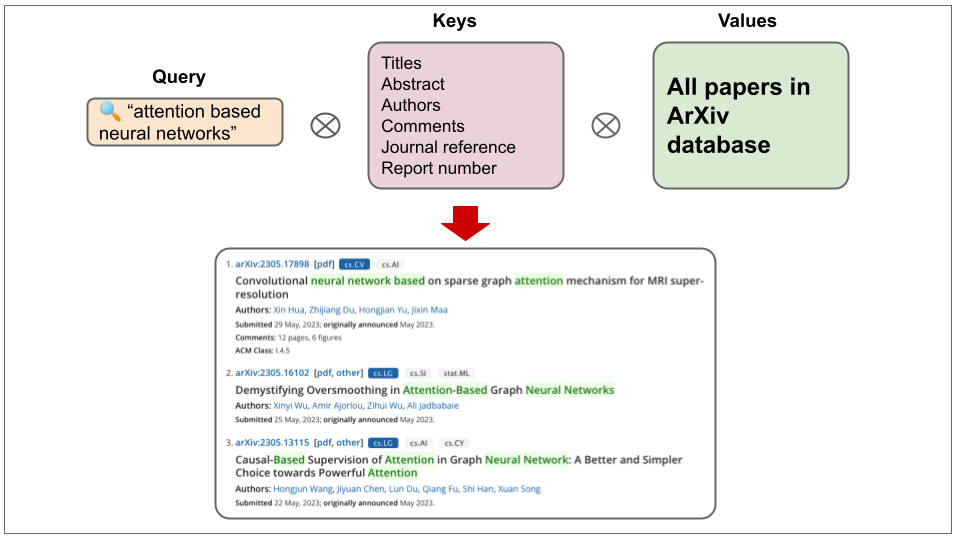

Query, keys, and values are terms commonly used in search engines and database systems. To understand those terms, let’s take a simple example1. Let’s say you are searching papers that are based on attention on ArXiv. The query is ideally what you will put in the search box. Internally, the ArXiv may organize papers by a set of predefined keys. Before ArXiv gives you papers that you asked for, it will compare your query to those predefined set of keys and return papers that best match with query and keys correspondence. Values merely refers to all papers in the database. As a disclaimer, we are using this example to understand the meaning of query, keys, and values in search and database systems context. It’s not an attempt to show how ArXiv system works.

Fig 9: Example demonstrating query, keys, and values in ArXiv paper search system.

With such intuitive understanding of query, keys, and values in mind, let’s move to the mathematical representation of the attention function.

Fig 9: Example demonstrating query, keys, and values in ArXiv paper search system.

With such intuitive understanding of query, keys, and values in mind, let’s move to the mathematical representation of the attention function.

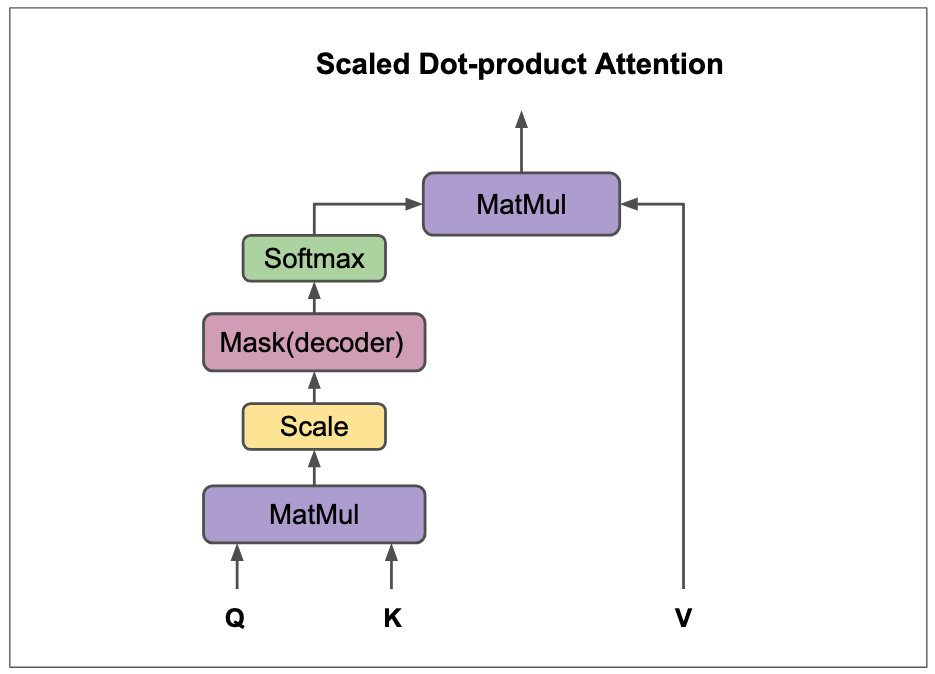

\[ Attention(Q,K,V)=\text{Softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V \]

From the function above, \(Q\), \(K\), \(V\) are query matrix, key matrix, value matrix respectively. We compute the dot product of query and keys and divide the product by a scaling factor of \(\sqrt{d_k}\). The scaling factor is used to avoid the scenarios where large values of \(QK^T\) would result in small gradients. Then, we normalize the dot product into a probability distribution with softmax(this basically give us weighted sum) and by multiplying it with values, we get weighted values.

*Fig 10: Graphical representation of dot-product attention. Figure adapted from [Vaswani et al. 2017](https://arxiv.org/abs/170⬤

*Fig 10: Graphical representation of dot-product attention. Figure adapted from [Vaswani et al. 2017](https://arxiv.org/abs/170⬤

The kind of attention described above is called scaled-dot product attention, a modified dot-product attention(Luong, Pham, and Manning 2015). There are other kinds of attention such as additive attention(Bahdanau, Cho, and Bengio 2014), content-based attention(Graves, Wayne, and Danihelka 2014), location-based attention(Bahdanau, Cho, and Bengio 2014), and general attention(Luong, Pham, and Manning 2015). Each of those attention types can either be applied globally(to the whole input data), hence global attention, or locally(sub-parts of the input data), hence local attention.

You may have heard that transformer is parallizable and you may be wondering where it comes from. Transformer parallization comes from attention function. Provided that both query, keys, and values are matrices, attention can be performed in two main matrix multiplies and hence no loops or any recurrent operation involved. Computing attention is resonably faster for GPUs. For bigger models(in order of billions parameters) and massive training data(in order of billion/trillions tokens), attention is can be expensive since it takes quadratic time complexity from the fact that each token attends other tokens.

If the queries, keys, and values are derived from same source, the attention applied to them is called self-attention. If they come from different source, we say cross-attention.

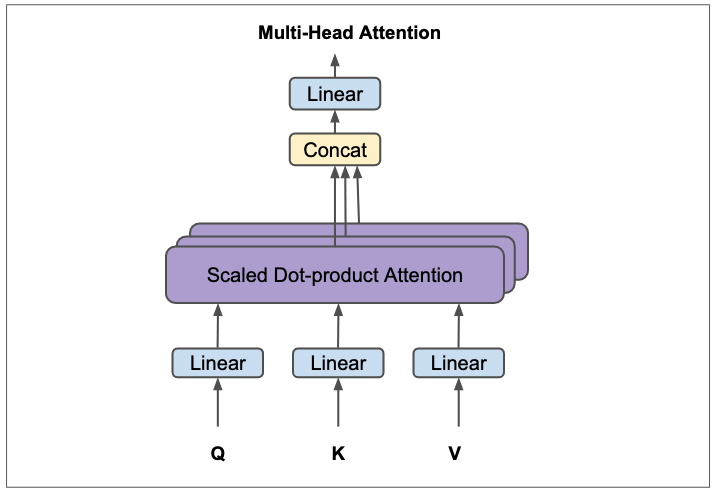

Multi-Head Attention

What we decribed above is a single attention layer. In practice, you typically would not get sound results with just one attention layer. Instead, people tend to compute multiple attention layers in parallel and concatenate the results. In nutshell, that is multi-head attention. Multi-head attention is basically multiple independent attentions computed over linearly projected QKV vectors. In the figure below of multi-head attention, the concatenated attention values are linearly projected to the model dimension.

Fig 11: Multi-Head attention. Figure adapted from Vaswani et al. 2017.

Fig 11: Multi-Head attention. Figure adapted from Vaswani et al. 2017.

As explained by the designers of the transformer architecture, computing multiple attentions in parallel allows the model to “jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces at different positions.” (Vaswani et al. 2017). A surprising thing about multi-head attention is that it doesn’t increase the overall computation cost because the dimension of each head is oneth of number of heads(i.e, heads in base transformer is 8) of the overall model dimension(ie, 512). So, if the dimension of the model (\(d_{model}\) in the paper) is 512, the number of heads in multi-head attention are 8, each head is thus \(512 / 8 = 64\).

Multi-head attention can be seen as depth-wise separable convolution(Chollet 2017) in ConvNets. Depth-wise separable convolution is a special type of convolution that splits input tensor into multiple channels, operate on each channel independently, concatenate the individual outputs and and feed the results to a pointwise convolution(1x1 convolution which is equivalent to a linear projection).

MLPs

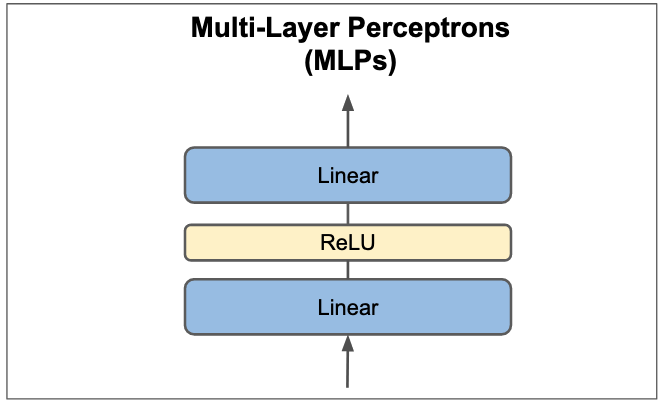

MLPs or Multilayer Perceptrons2 are one of the two sublayers in both encoder and decoder. MLPs in the transformer are made of two linear layers with ReLU activation in between and they are applied to each position independently and identically.

Fig 12: Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP) in transformer.

Fig 12: Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP) in transformer.

Embeddings and Positional Encoding Layers

The transformer architecture incorporates two embedding layers: one at the encoder to handle the input or source sequence, and another at the decoder for handling target or output sequence. These embedding layers convert input or output tokens into dense vectors of a fixed size, essentially mapping each token in a sequence to a specific dense vector. Utilizing embeddings is a standard practice in language modeling due to the semantic depth they provide. With these embedded token vectors, those bearing similar semantic meanings tend to align in the same direction.3

The size of the embeddings in the base transformer is 512(this is the dimension of the whole model). As a side note here, transformer architecture maintains the same dimension across the whole network and it is 512 for base model. This is what referred to as \(d_{model}\) previously.

Positional encodings serve as integral components in the initial stages of both the encoder and decoder within a Transformer model. They are used to preserve the order of tokens in a sequence. One might question the necessity of these positional embeddings. This stems from the inherent permutation invariance of the attention mechanism, whereby modifying the order of tokens does not alter the output weighted values4. Consequently, the attention mechanism, on its own, lacks awareness of the token order. As the transformer architecture does not incorporate any other recurrence methods, positional encodings are introduced to equip the model with positional awareness of the tokens in the sequence. In essence, without positional encodings, a Transformer would indeed exhibit permutation invariance. However, such a design would fall short for tasks where sequence order holds significance, as is the case for most NLP tasks.

For encoding positional information in a sequence, the designers of transformer used sinusoidal functions of different frequencies. They also experimented with learned positional embeddings, but it did not make a difference in the results.

Residual Connections, Layer Normalization, and Dropout

Residual connections are at the heart of neural network design and they are one of the popular ingredients in modern deep learning. Since when deep residual networks proved substantial performance in computer vision(He et al. 2016), residual connections have been used in almost most neural networks not just in vision but in other modalities as well. In fact, it is almost impossible to see a neural network model that does not use residual connections in present times. Residual connections alleviate unstable gradient problems and they help the model to converge faster.

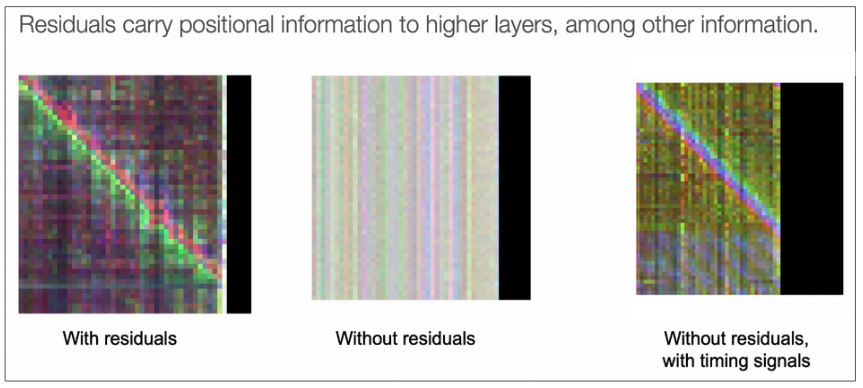

One of the transformer authors, Ashish Vaswani once said that “redisual connections carry positional information to higher layers, among other information.” Take a look at the image below!

Fig 13: Residual connections carry signals to higher layers which improves the training of the transformer model. The smooth diagonal in the first image (with residuals) shows the effectiveness of residual connections. Image by Ashish Vaswani in CS224N.

Fig 13: Residual connections carry signals to higher layers which improves the training of the transformer model. The smooth diagonal in the first image (with residuals) shows the effectiveness of residual connections. Image by Ashish Vaswani in CS224N.

Layer normalization(Ba, Kiros, and Hinton 2016) is also one of the most used normalization techniques in modern neural networks. Layer normalization significantly reduces the training time by normalizing the activations of a layer with the layer mean and variance. Unlike batch normalization(Ioffe and Szegedy 2015) that normalizes each layer with mean and variance computed over the mini-batch, layer norm just normalizes each layer with the mean and variance of each activation. Layer normalization maintains similar behavior during both training and testing phases, unlike batch normalization which exhibits different behaviors in these two stages.

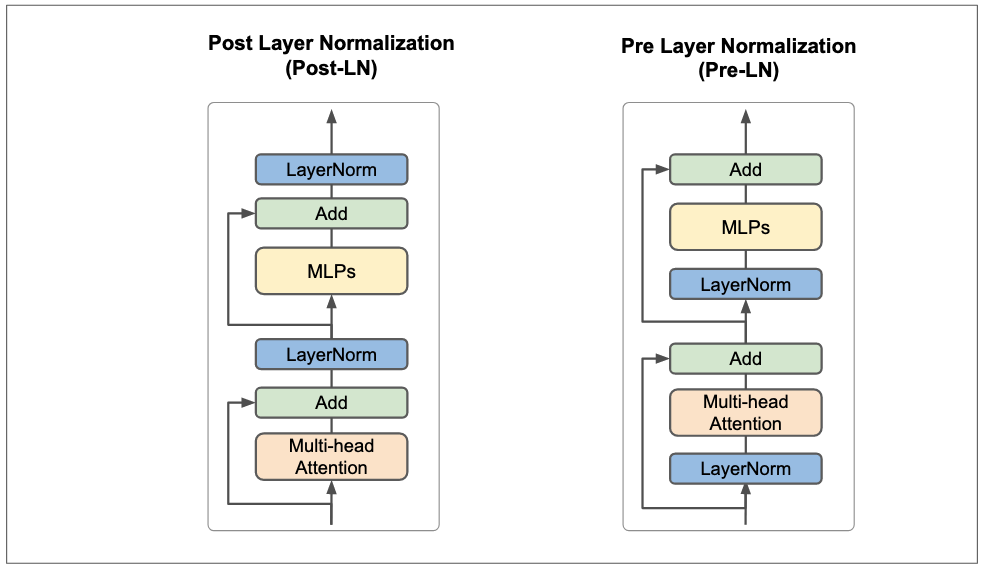

There are two ways to place layer normalization in transformer architecture. The first option is called Post layer normalization(Post-LN) where layer normalization is placed between residual blocks(or after each sublayer(multihead-attention and MLPs) but after addition). The second option is called Pre layer normalization(Pre-LN) where layer normalization is placed before each sublayer inside the residual block. The standard transformer architecture uses Post-LN, but in the updated codebase that trained the orginal transformer5, it was found that to be Pre-LN. This mismatch between paper and codes makes it hard to trace back the actual position of layer normalization in initial transformer but from the commit history, it looks like Pre-LN was used later. The authors could have updated the paper but they probably didn’t mind since no one knew this would turn out to be one of the influential and reference papers in neural network design.

Fig 14: Post layer normalization (Post-LN) and Pre layer normalization (Pre-LN).

Fig 14: Post layer normalization (Post-LN) and Pre layer normalization (Pre-LN).

Thus, it’s not exactly clear where the layer normalization should be and this is an active research question. A recent study on the impacts of Pre-LN and Post-LN(Xiong et al. 2020) showed that placing layer normalization before multi-head attention and MLPs(Pre-LN) improves the training and converge much faster than layer normization placed after multi-head attention and MLPs. The study also claimed that with Pre-LN, you don’t need to be smart at choosing learning-rate scheduler since Pre-LN have better initializations. Neither of Pre-LN an Post-LN is perfect. Another quite recent study introduced ResDual(Xie et al. 2023) which basically alleviates issues of Pre-LN and Post-LN by introducing additional residual connection with layer normalization.

Where you should place layer normalization continue to be a question but this should be less of a question. As many people have noted, transformer seems to be a universal architecture. The orginal vanilla transformer(with few tweaks like yes LN) is the one that is still behind most novel works in language modelling, visual recognition, and multimodal learning depsite millions number of works that claims to improve the transformer. Thus, we should aim to keep the universality of this architecture. We will see this more in efficient transformers toward the end of the article.

Before we wrap up this section, let’s talk about dropout(Srivastava et al. 2014) in the transformer architecture. Layer normalization can acts as a regularizer as a side effect but you still need other forms of network regularizations to deal with overfitting. Dropout is applied to the output of each sublayer(before addition and normalization). It is also applied to the sum of the embeddings and the positional encodings in both encoder and decoder stacks. For other regularization techniques used in training transformer and other training details, check out the paper for more.

Linear and Softmax Layers

The linear layer after decoder takes the decoded activations and project them to the size of the vocabulary. This linear layer will basically produce logits. The softmax layer will take those logits and turn them into next-token probabilities. The next predicted token will be basically the argmax of softmax output.

Visualizing Attention

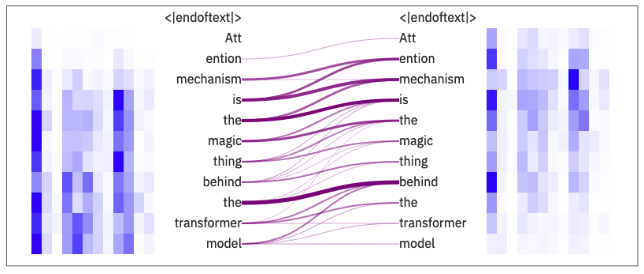

Attention can capture the overall context from an input sequence, which often leads to better performance of the model. By visualizing attention, we can see which parts of the input sequence have significant influence on the model’s output. This helps us better understand how the inner workings of Transformer neural networks.

Fig 15: Visualizing attention with ExBert.

Fig 15: Visualizing attention with ExBert.

The figure above depicts the attention heads on \(8^{th}\) layer of GPT-2 (Radford et al. 2019). From the figure, it’s clear that even in the early layers of the transformer, most tokens attend to each other.

A number of tools that visualize attention have evolved overtime to help the deep learning community understand what’s going inside the transformer model. One of the most famous tools is BertViz (Vig 2019)6. ExBert that we used to make the above visualization is also an excellent and simple tool for visualizing the attention on most transformer based models such as GPT-2 and BERT(Devlin et al. 2019).

The Pros and Cons of Attention

The attention mechanism has resulted in a significant shift in sequence modelling and other modalities that can be framed as sequences. When compared with other sequence networks such as recurrent networks and 1D convolutions, attention offers numerous advantages. These are briefly discussed below:

Long-term Dependencies: Traditional Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), including variants like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), are prone to the issue of long-term dependencies, where the model’s ability to retain information weakens over time. Attention mechanisms help mitigate this problem by enabling the model to directly access any point in the input sequence, thereby preserving the overall context.

Parallelization: Unlike RNNs, which require sequential computation, attention-based models, such as transformer architectures, can process all tokens in the input sequence in parallel. This makes them more computationally efficient and scales better with current hardware accelerators.

Interpretability: Attention provides a certain degree of interpretability, as it highlights the parts of the input that the model considers most important for producing a particular output. The “attention map” can help us understand what the model is “thinking.”

Global Context: In Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), the receptive field is typically local and depends on the kernel size, potentially leading to the loss of broader context. However, with attention, each output token can take into account information from every token in the input sequence, thus preserving the global context.

Improved Performance: Attention-based models, especially those that utilize transformer architectures, have achieved state-of-the-art performance in many NLP tasks, outperforming their RNN and CNN counterparts. They have also pushed envelope in other modalities such as computer vision, speech recognition, robotics, multimodal learning, etc…

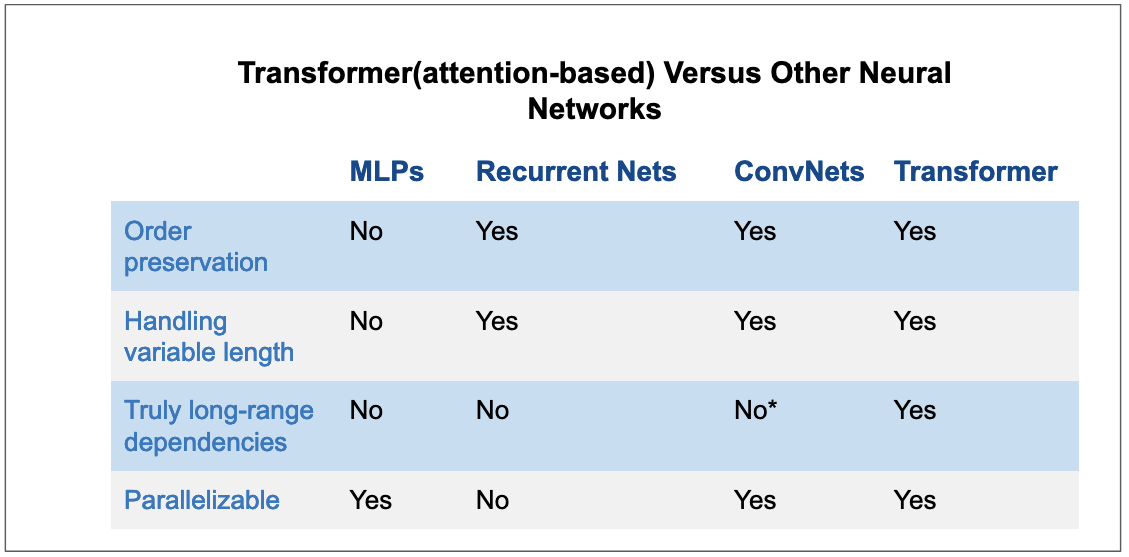

In the figure below, we summarize the properties of attention-based models versus other deep neural network architectures.

In the figure below, we summarize the properties of attention-based models versus other deep neural network architectures.

< Fig 16: Attention versus other recurrent network architectures. Transformer possesses nearly all good traits of neural networks. ConvNets are close to transformer but they require many layers to achieve long-range dependencies.

Despite the multitude of advantages they offer, as everything else in life, attention mechanisms also come with their fair share of challenges. For instance, in several types of attention, both memory consumption and computational cost can scale quadratically with sequence length. Various strategies, such as sparse attention or local attention, have been proposed to alleviate these issues but most of them are rarely used in practice(Tay et al. 2020).

Fig 16: Attention versus other recurrent network architectures. Transformer possesses nearly all good traits of neural networks. ConvNets are close to transformer but they require many layers to achieve long-range dependencies.

Despite the multitude of advantages they offer, as everything else in life, attention mechanisms also come with their fair share of challenges. For instance, in several types of attention, both memory consumption and computational cost can scale quadratically with sequence length. Various strategies, such as sparse attention or local attention, have been proposed to alleviate these issues but most of them are rarely used in practice(Tay et al. 2020).

While transformers offer the advantage of parallelization during training, the nature of the inference process may still necessitate a sequential approach, contingent on the specific task. Due to their autoregressive nature, transformers generate outputs one token at a time, continuing this iterative process until the desired output sequence is fully produced.

Furthermore, while attention offers a certain level of interpretability, it is far from perfect. Although it provides some insights into the model’s functioning, fully deciphering complex models based solely on attention maps can be, to say the least, a daunting task, if not almost impossible.

Large Language Transformer Models

Evolution of LLMs

Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized human interaction with machine learning systems. Natural language interfaces, such as ChatGPT and Bard, are powered by robust LLMs. These models have paved the way for executing natural language downstream tasks on-fly or through zero-shot learning. Such tasks, in the past, necessitated the gathering of a downstream or task-specific datasets.

At the core of these LLMs, it’s fundamentaly a transformer model that we have seen with little tweaks here and there. In this section, we will delve into the compressed evolution of Large Language Models. Moreover, we will explore the development of vertical LLMs, specifically designed and fine-tuned for particular applications.

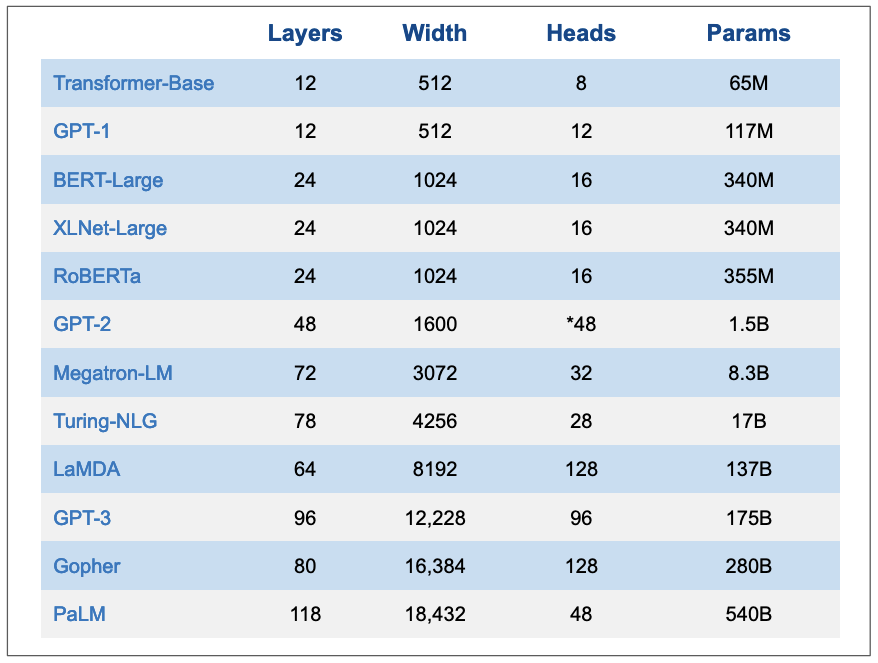

Transormer base model had 65M parameters but since then, language models got bigger and bigger(in order of billions) and hence the name large language models. Below is a quick overview of popular large language models.

Fig 17: Overview of popular LLMs. Layers are the number of stacked encoders/decoders or both for encoder-decoder models, width is the dimension of the model, heads are the number of attention layers in multi-head attention, and params are the number of parameters. N.B, the number of heads in GPT-2 are not exactly known.

Fig 17: Overview of popular LLMs. Layers are the number of stacked encoders/decoders or both for encoder-decoder models, width is the dimension of the model, heads are the number of attention layers in multi-head attention, and params are the number of parameters. N.B, the number of heads in GPT-2 are not exactly known.

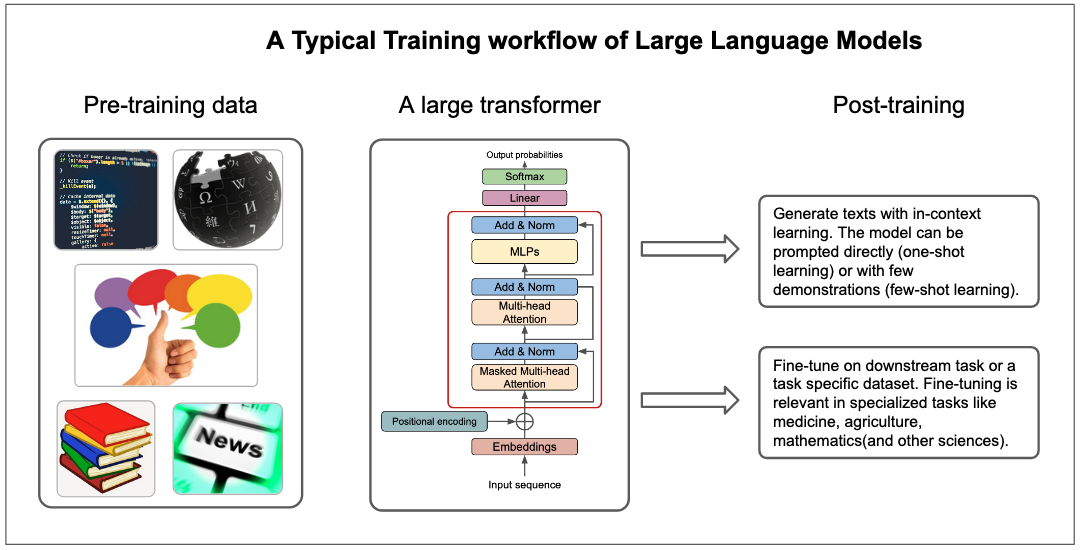

The training process for most large language models (LLMs) follows a broadly similar pattern. In the initial pretraining phase, LLMs are exposed to vast volumes of curated textual data, sourced from a diverse range of materials such as books, articles, code snippets, and websites. This vast dataset is essential for the models to gain a comprehensive understanding of the world, enabling them to create rich representations and generate contextually relevant responses. The general public holds high expectations for LLMs’ performance across various domains. To meet these expectations, the pretraining data must encompass a wide spectrum of topics and disciplines(J. Yang et al. 2023).

The actual training of LLMs occurs in an unsupervised fashion, with a specific focus on self-supervised learning(SSL). This approach eliminates the need for labelled data, a crucial feature considering the near-impossibility of labeling the entirety of online content.

Fig 18: A typical training workflow of large language models. LLMs are typically trained on large unlabelled datasets. After training, they can be used directly via prompt engineering or fine-tuned further on specialized tasks.

Fig 18: A typical training workflow of large language models. LLMs are typically trained on large unlabelled datasets. After training, they can be used directly via prompt engineering or fine-tuned further on specialized tasks.

However, training models on unlabelled data requires the clever implementation of training objectives since there is no ground truth for reference. Most LLMs, therefore, utilize the next-token prediction (NTP) as a common training objective. In essence, the LLMs are taught to accurately predict the next token in a sequence, gradually enhancing their understanding and generating capabilities. Another commonly used training objective is masked language modelling(MLM). Masked language models are trained to predict a masked token in a sequence. This objective was popularized by BERT(Devlin et al. 2019).

After pretraining phase, the models can be used to generate texts via techniques like zero-shot learning or few-shots learning. In zero-shot learning, a model is prompted to perform a task(or answer a given question) without any demontrations of how the task is done. In few-shots learning, a model is given a number of demonstrations of how the task is done before it can be asked to perform that task. Zero-shot learning and few-shot learning are examples of in-context learning. In-context learning(ICL) refers to the ability of LLMs to generate coherent texts using semantic prior knowledge(Jerry Wei et al. 2023) and without any parameter updates(Akyürek et al. 2023). Prompting large language models(also known as prompt engineering) is a relatively new field itself and there are other prompt engineering techniques such as chain of thoughts(CoT)(Jason Wei, Nye, and Liang 2022).

In-context learning tends to excel at tasks that are considered simple but falls short for tasks that can not be described easily in prompts. Complex tasks requires more than clever prompts. In the words of Karpathy, “reaching top tier performance(on complex tasks) will include finetuning, especially in applications with concrete well-defined tasks where it is possible to collect a lot of data and”practice” on it.”7. Thus, for LLMs to get good performance on specialized tasks like mathematics, medicine, scientific fields(like chemistry), people typically finetune base LLMs on downstream datasets. We will see examples of this in the section of vertical LLMs.

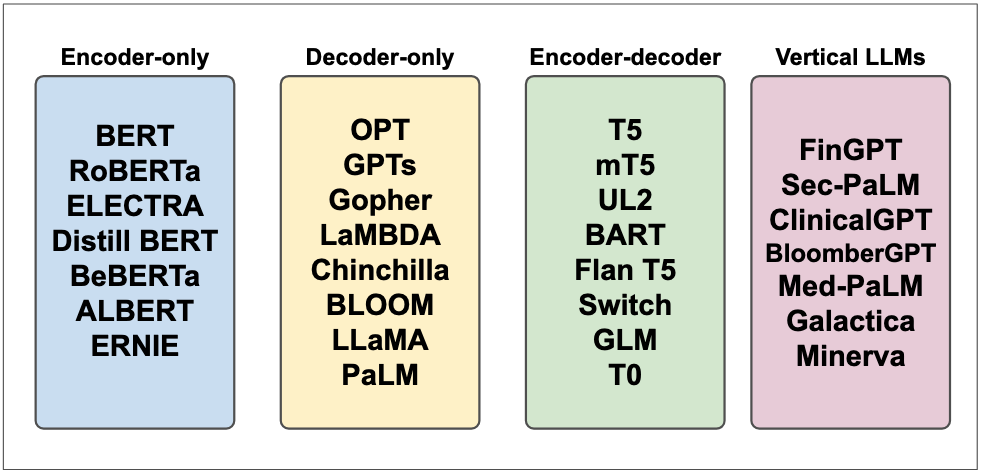

Now that we’ve briefly introduced Large Language Models (LLMs), it’s time to examine some of the most popular LLMs, focusing specifically on their design choices: whether they function as encoders, decoders, or employ a combined encoder-decoder architecture.

Encoder, Decoder, Encoder-decoder LLMs

The standard transformer model has encoder-decoder and this has to do with the task it was meant to perform which is machine translation where you have to process both input sentence and its target translation. Since the transformer, AI research community came up with different variations of the architecture for different tasks. Depending on the task, some transformer models maintained encoder-decoder structure, some used decoder only or encoder only. Let’s start with the latter.

Encoder-only LLMs

Encoder-only LLMs use the encoder part of the standard transformer model. Encoder-only LLMs are typically used for NLP discriminative tasks such as text classification and sentiment analysis.

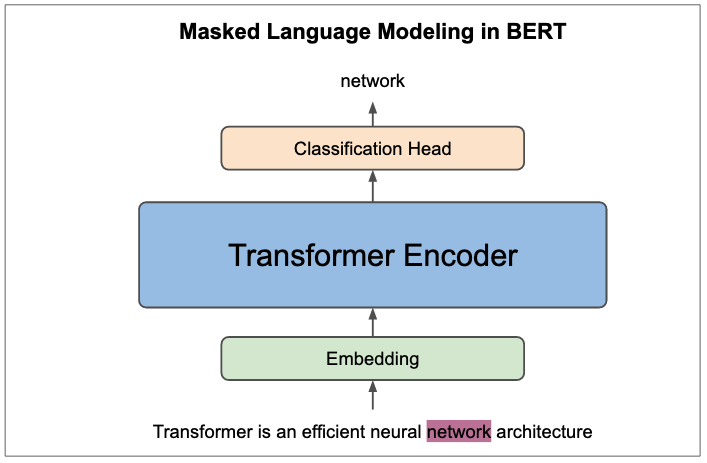

BERT(Devlin et al. 2019) is one of most popular encoder-only language models. BERT is one of the earliest works that showed that you can pretrain a transformer(encoder) on large unlabeled text dataset and finetune the same architecture on various downstream tasks with additional task-specific head. The pretraining objectives for BERT were masked language modelling(MLM) and next sentence prediction(NSP)8. With masked language modeling, we mask a given percentage(15% as noted in the paper) of input tokens and the goal is to predict the masked tokens. In next sentence prediction, for two sentences pair making up the input sequence, the goal is to predict whether or not two sentences are in a correct order at random.

Fig 19: Masked language modelling (MLM) in BERT. In the sentence example shown in the figure, the objective of training BERT is to predict the masked word “network”. In the next sentence prediction objective, the workflow is roughly the same but instead of predicting the masked tokens, we predict if two sentence pairs separated by the SEP token are in the correct order.

Fig 19: Masked language modelling (MLM) in BERT. In the sentence example shown in the figure, the objective of training BERT is to predict the masked word “network”. In the next sentence prediction objective, the workflow is roughly the same but instead of predicting the masked tokens, we predict if two sentence pairs separated by the SEP token are in the correct order.

BERT is a truly revolutionary technique that improved SOTA on ubiquitous number of NLP downstrea tasks. It also inspired other efficient bidirectional architectures for NLP pretraining such as RoBERTa(Y. Liu et al. 2019) standing for Robustly optimized BERT approach. One of the main design choices that RoBERTa introduces is not using next sentence prediction objective.

Decoder-only LLMs

Decoder-only LLMs are based on the decoder part of standard transformer. In transformer architecture, decoder is highly similar to encoder except that the self-attention in decoder is masked to prevent the model to look at subsequent tokens when generating current token.

Decoder LLMs are trained with next token prediction objective9. As a result, they can only generate one token at time or autoregressively. Overally, decoder models are used in generative tasks.

The most popular decoder models are GPT(Generative Pretrained Transformer) models family, most notably GPT-3(Brown et al. 2020) and GPT-4(OpenAI 2023). GPT-3 and GPT-4 are direct scale-up of the early GPT model(Radford et al. 2018). As any other large language model, GPT models are trained on massive amount of unlabelled data(in order of billions to trillions tokens). Due to the large-scale pretraining and suitable training objective, GPT models develops impressive in-context learning capabilities where they can perform a range of NLP downstream tasks without gradient updates or task-specific fine-tuning(Brown et al. 2020). In fact, GPT models can perform tasks like text classification, summarization, question answering on-fly by just prompting the model in zero-shot or few-shot settings10. This remarkable feat of in-context learning has often been called “emergent abilities” of large language models(Jason Wei et al. 2022).

GPT models are not the only models based on decoder. In fact, most famous LLMs are decoders. Examples include PaLM(Chowdhery et al. 2022), BLOOM(Le Scao et al. 2022), Chinchilla(Hoffmann et al. 2022), LLaMA(Touvron et al. 2023), and many others.

Encoder-Decoder LLMs

Encoder-decoder LLMs looks like the standard transformer. They are generally used in tasks that demands processing two sequences(i.e, input and target are both sequences) such as machine translation. Encoder-decoder style is not widely used compared to other model styles we have seen. The most famous models of this kind are T5(Raffel et al. 2019), BART(Lewis et al. 2019), UL2(Tay et al. 2022), FlanT5(Chung et al. 2022), mT5(Xue et al. 2021), etc…

Encoder-decoder style is also used in multimodal learning, most notably vision-language pretraining(VLP). Works like SimVLM(Z. Wang et al. 2021) and PaLI-X(X. Chen et al. 2023) employs encoder for learning joint image and text representations and decoder for generating the output.

Vertical LLMs

Most of LLMs that we outlined above are typically referred to as foundational or frontier LLMs. Foundational models are typically trained on massive amount of data with self-supervision and they can be fine-tuned to a wide range of downstream tasks(Bommasani et al. 2022).

Vertical LLMs are a class of LLMs that are adapted to specific applications. Foundational LLMs can generalize to simple tasks like sentiment analysis but they don’t perform well on complex tasks or tasks that require a domain expertize. For example, a foundational LLM is unlikely to perform well on medical question answering task because it doesn’t have expertize in medicine. More examples: a foundational LLM is unlikely to perform well on legal question answering task because it doesn’t have expertize in law. This is also true in other fields such as finance, physics, chemistry, etc…Vertical LLMs are designed to address this issue. They are trained on a specific domain and they can perform well on tasks that require expertize in that domain. Foundational models aim to be generalists but most of the time, we care about models that can do one thing very well.

Examples of recent vertical LLMs include MedPaLM(Singhal et al. 2022) and Med-PaLM 2, ClinicalGPT(G. Wang et al. 2023), FinGPT(H. Yang, Liu, and Wang 2023), BloombergGPT(Wu et al. 2023), Galactica(Taylor et al. 2022), Minerva(Lewkowycz et al. 2022), among others.

Fig 20: LLMs Topologies. Adapted from J. Yang et al. 2023.

Fig 20: LLMs Topologies. Adapted from J. Yang et al. 2023.

Transformers Beyond NLP: Vision and other Modalities

Transformer was introduced for Natural Language Processing(NLP) domain, more precisely, for neural machine translation. In no time, transformers outperformed prior neural networks on most NLP tasks and quickly expanded into other modalities. In this section, we will discuss in brief the emergence of transformers in visual recognition and other modalities.

Visual recognition is one of the earliest modalities that was significantly impacted by transformers. For a long time, ConvNets were state of the arts in visual recognition. It’s thus a critical to ask why researchers care about alternatives to ConvNets. The main downside of ConvNets is their spatial inductive biases11.

One of the earliest applications of transformer to image processing is Image Transformer (Parmar et al. 2018) which approached image generation as an autoregressive problem, analogous to text generation. The Image Transformer was a standard transformer applied to a sequence of pixels, trained to generate these pixels autoregressively until it created the complete image. This was a great idea, but as it turns out, images typically have large resolutions, and thus, it was not feasible to apply self-attention to images of 256x256 for instance. There were several works attempting to apply transformer to image domain but one of the first successful works was Vision Transformer(Dosovitskiy et al. 2021) that applied the transformer encoder to a sequence of images patches. ViT overcame the computational complexities of self-attention by image patchification idea, marking a significant step in extending transfomers to computer vision domain.

As we saw early, a huge contribution of transformers successes in NLP was unsupervised pretraining on massive amount of unlabelled data. The success of Vision Transfomer was also attributed to millions of training images, JFT-300M(C. Sun et al. 2017) although later works like MAE(He et al. 2021) and (Steiner et al. 2021) achieved resonably good performance on classical computer vision benchmarks such as ImageNet. MAE is an encoder-decoder self-supervised model that follows BERT pretraining objective of predicting randomly masked patches while the later explores clever augmentations and regularizations to train ViT. ViT has been used as backbone in many influential papers such as CLIP(Radford et al. 2021), DALLE•2(Ramesh et al. 2022), Stable Diffusion(Rombach et al. 2022), among other recent works in visual language models. Aside from ViT enabling joint modelling of vision and language, it has also been augmented with convolutional neural networks to get both worlds in computer vision downstream tasks. Notable works of ConvNets and Vision Transformer topology are DETR(Carion et al. 2020), PatchConvNet(Touvron et al. 2021), MobileViT(Mehta and Rastegari 2022), among others.

Vision and language are two of the most important modalities when it comes to human to computer interaction and it’s not surprising that most works incorporating transformers have been in language, vision, or visual language learning. That said, transformers have been used in other modalities such as reinforcement learning(L. Chen et al. 2021), robotics((Brohan et al. 2022), RoboCat(Bousmalis et al. 2023)), and speech recognition(Radford et al. 2022). Finally, works such as Gato(Reed et al. 2022) and ImageBind(Girdhar et al. 2023) have gone further in modelling pretty much all modalities.

Transformer has established itself as universal architecture and recent works across different modalities prove that, but there are still challenges.

Transformer: Current Challenges and Future Directions

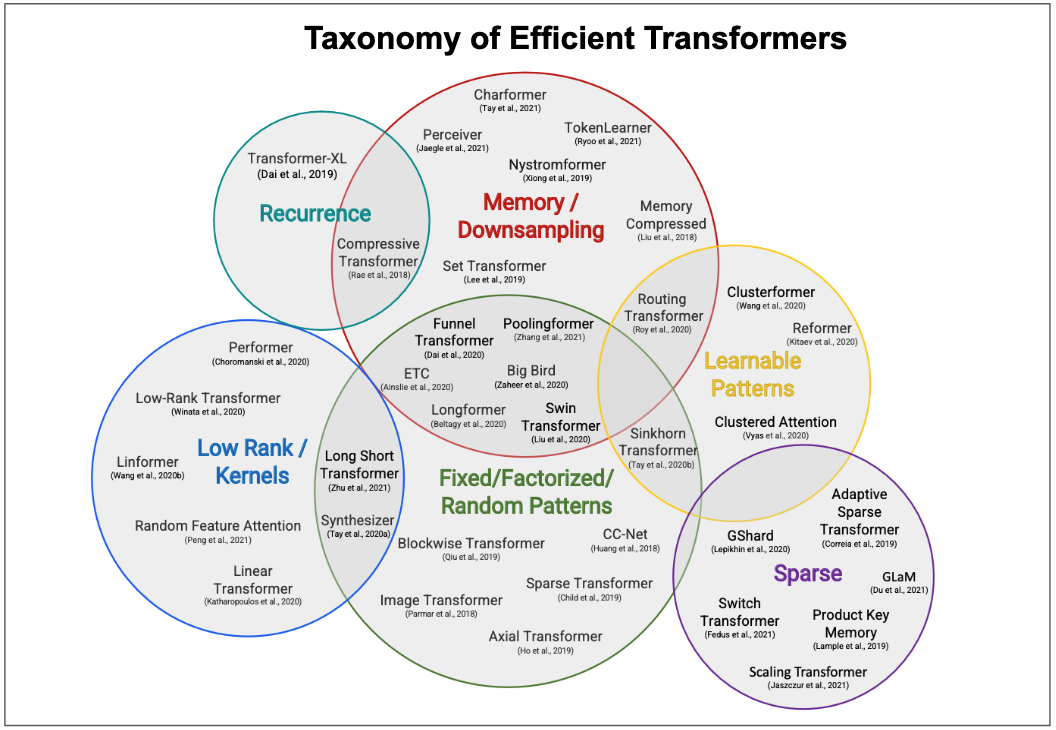

Efficient Transformers

Transformer has shown significant performance across various modalities such as language, vision, robotics, and reinforcement learning. Transformer neural network architecture has a set of traits that make it a suitable architecture for those domains: it is expressive, plays well with current optimization techniques, and it can be parallized. From those traits, one can say that transformer is an efficient architecture. That said however, the efficiency of transformer comes with enormous computatation cost due to the quadratic time and memory complexity of self-attention. The compute requirements of transformer has limited its scalability and its applications in low-budget devices such as smartphones and microcontrollers.

Model efficiency is an important thing to take into account when developing and deploying machine learning systems because how a model perform during inference can affects user experience(Dehghani et al. 2022). There has been zillion transformer models that claim to improve the efficiency(memory footprint and computational cost) of transformer architecture(those models are typically called “xformers”) but those models usually tend to be targeted at one particular benchmark or device. Most of the new xformers models that claim to reduce the quadratic time and memory complexity of self-attention are much slower than vanilla transformer and they are rarely used in practice and they don’t have the universality of original transformer(Tay et al. 2020).

As (Tay et al. 2020) puts it nicely in a survey of “Efficient Transformers”, the ideal xformer should yes reduce the quadratic time complexity of self-attention, but should stay universal and perform well across all tasks and modalities. It should also not trade-off speed for memory, should not be hard-engineered, should stay elegant and simple. For more, I recommend you read the survey paper of efficient transformers.

Fig 21: A taxonomy of efficient transformers. Image from Tay et al. 2020.

Fig 21: A taxonomy of efficient transformers. Image from Tay et al. 2020.

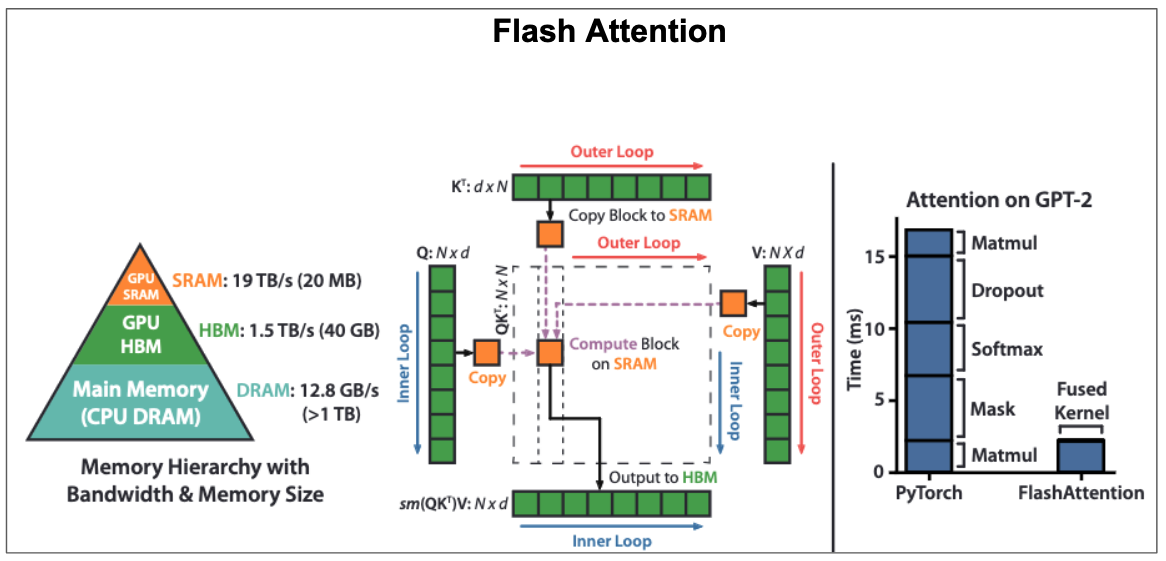

Virtually all modified transformer models compute the approximation of attention to reduce the cost down. As opposed to those approaches, there is actually one kind of attention that computes exact standard attention values but way faster. That approach is FlashAttention(Dao et al. 2022) and we will talk about it on a high-level.

FlashAttention is fast and memory-efficient algorithm that computes the exact attention. FlashAttention is 2-4x faster than standard attention. It achieves this enormous increase in compute efficiency by using two main techniques: tiling and recomputation. Tiling happens in forward pass and it involves splitting large matrices in attention(K key and V value) into blocks. Rather than computing attention over entire matrices, FlashAttention computes it over blocks and concatenate the resulting blocks saving a huge amount of memory. Recomputation happens in backward pass and it basically means recomputing the attention matrix rather than storing it in forward. The idea of FlashAttention boils down to improving the memory and not decreasing computations because modern GPUs have high theorical FLOPs(Floaping Point Operations, means you want to max that out) but limited memory12(means any saving in memory can improve the training speed). HBM(High Bandwidth Memory) is typically large but it is not faster than on-chip SRAM(Static Random Access Memory) and thus, the computations over blocks(of K and V) happens in SRAM(because it is faster) but all full matrices are stored in HBM(because it’s big). This high-level explanation is probably oversimplication provided that FlashAttention is implemented at the GPU level(with CUDA software) and this is in fact the reason why it is IO aware but hopefully that explain what’s going on in this fast algorithm.

Below image shows the memory hierarchy in GPU, FlashAttention algorithm, and amount of time(in ms) taken by each intermediate step in GPT-2 attention versus FlashAttention. Ideally, we would want the bulk of computations to be taken by matrix multiplication(matmul) operations but surprisingly, dropout, softmax, and mask(i.e, GPT-2 is decoder model) end up taking the whole runtime in GPT-2 attention because they are computed over full matrices. Matmuls take less runtime than those other operations because GPUs are exactly designed to be fast at matrix multiplications(they have really high theorical FLOPs and maximizing FLOPs usage doesn’t reduce the runtime). By using tiling and recomputation techniques, the compute time of FlashAttention is significantly low compared to standard attention as you can see below.

Fig 22: The memory hierarchy in GPU, FlashAttention algorithm, and runtime of GPT-2 attention vs FlashAttention.

Fig 22: The memory hierarchy in GPU, FlashAttention algorithm, and runtime of GPT-2 attention vs FlashAttention.

FlashAttention is intergrated in PyTorch 2.0, Hugging Face transformers, Microsoft’s DeepSpeed, MosaicML composer library and many other library. You can learn more FlashAttention in the paper, or watch this video by core author, and the release blogpost. At the time of writing this section, FlashAttention2(Dao 2023) was also released and it is even faster than FlashAttention version 1 on several orders of magnitude. FlashAttention-2 improves parallelism by parallelizing over sequence length dimension instead of batch size and number of attention heads and splits Q(query) matrix instead of K and V. This release blog post explains well what FlashAttention2 brings to the tensor table.

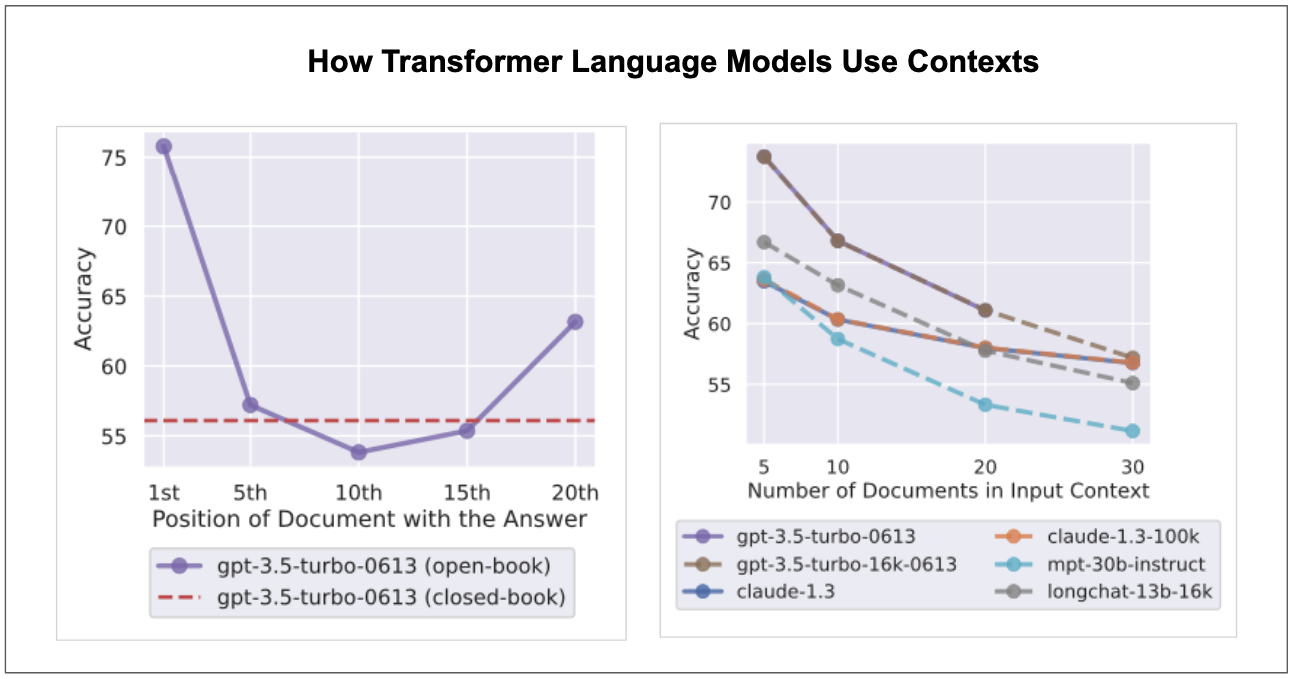

Transformers with Effective Long Contexts

Handling long context length is one of the main active areas of research in Transformer large models. As direct consequence of the quadratic time and memory complexity of attention, transformer fails to process long context windows. Researching techniques that extend the context window of transformer architecture is an important thing since context window determines the amount of information that you can fit in transformer memory during inference. Tasks like long conversations, summarizing long documents, and executing long-term planning may require models that support long context windows(S. Chen et al. 2023).

Alot have been written about context windows and extending them such as (S. Sun et al. 2021), but I want to highlight a recent paper that presents remarkable findings around long contexts. Recents language models(based on transformer) can takes longer contexts but it’s not clear whether long context actually helps. As shown by (N. F. Liu et al. 2023), the performance of language models degrades with increase in input context length. So, even for models that have extended context length, their performance still degrades for longer input contexts. Also, the work also found that language models perform well when the relevant information are placed at the beginning or the end of the input context and significantly degrades when the relevant information are placed in the middle, suggesting that language models are U-shaped reasoners.

The findings highlighted above are appealing and provide broad implications that could be applicable in the design of fine-tuning datasets and during in-context learning, but it’s important to note that none of those is established understandings provided that “how transformer models perform on long context windows” is an active area of research. We hope that future transformer models will be able to operate over long input sequences and at the same time performing well regardless of relevant information are placed. This is in fact the holy grail of large language models.

Fig 23: Language models (based on transformer) tend to perform well when relevant information is at the beginning or at the end of the input context (graph on the left), and their performance decreases for longer contexts (graph on the right). The graphs are taken from N. F. Liu et al. 2023.

Fig 23: Language models (based on transformer) tend to perform well when relevant information is at the beginning or at the end of the input context (graph on the left), and their performance decreases for longer contexts (graph on the right). The graphs are taken from N. F. Liu et al. 2023.

Multimodal Transformer

A primary objective in neural network design is to architect a single, universal model that can efficiently process multiple modalities without necessitating modality-specific encoders or preprocessing. Indeed, transformer models have seen widespread application across various domains, spanning text, images, robotics, and speech. Yet, the goal of creating a truly universal transformer — one that performs equally effectively across all modalities without requiring specific adjustments — remains a challenge. This challenge arises from the inherent differences and complexities in data types and the transformer model itself, which frequently demand modality-specific modifications.

For instance, the process for handling text, images, and speech each have unique considerations due to their individual characteristics. Transformers excel in scenarios where data can be framed as a sequence of tokens, however, the method of transposing a particular modality into such a sequence significantly varies among different modalities. Consequently, the challenge lies in designing a singular architecture that can uniformly extract valuable insights from all data types with comparable efficiency.

The achievement of such an architecture would signify a monumental stride in the field of multimodal learning, paving the way for models that can seamlessly transition between different types of data and potentially unlocking new avenues of exploration in multimodal representation learning.

Nearly all current state-of-the-arts in multimodal learning typically uses separate tokenizer and encoder for each modality and most of them are also designed for visual language learning. This section doesn’t dive deep into the specifics of current multimodal approaches based on transformers but we provide examples for people interested in diving deep: Flamingo(visual language)(Alayrac et al. 2022), Gato(Reed et al. 2022), ImageBind(Girdhar et al. 2023), OFA(P. Wang et al. 2022), Unified-IO(Lu et al. 2022), Meta-Transformer(Y. Zhang et al. 2023), among others.

Virtually all transformer challenges stem from its extreme compute and memory requirements. Truly efficient transformers such as FlashAttention could potentially alleviate those challenges.

Open-source Implementations of Transformer

The original transformer model was implemented in Tensor2Tensor library13 but this was deprecated recently. The successor of of Tensor2Tensor is Trax which is based on JAX14.

There are many open-source implementations of transformer model architecture. Let’s briefly talk about three of most popular implementations. HuggingFace Transformer library(Wolf et al. 2020) is arguably one of the most popular implementations of transformers. The library simplifies inference pipelines for NLP(and vision) downstream tasks and can be used to train or finetune transformer-based models. HuggingFace Transformer library is easy to use, it’s clean, and has a large community of developers and contributors. minGPT and nanoGPT by Andrej Karpathy are also popular implementations in open-source and research community. Furthermore, x-transformers provides concise and experimental implementations of various transformer models usually from new research papers.

Lastly, it’s unlikely you will need to implement transformer model or part of it from scratch because modern deep learning frameworks such as PyTorch, Keras, and JAX(Via Flax) provides its implementation as layers that you can import easily just like how you import convolution or linear layers.

Supplementary Resources

This article contributes to an existing pool of knowledge surrounding the understanding of transformer neural network architecture. Therefore, it would be remiss not to highlight some invaluable resources on transformer architecture, which we will briefly provides below:

- The Annotated Transformer: This is one of the best and practical resources. It provides line-by-line implementation of transformer architecture, with completelu usable code. The original version was written by Sasha Rush and recent version was written by Austin Huang and his colleagues.

- Let’s Build GPT from Scratch by Andrej Karpathy: This is arguably the best resource regarding implementations of transformer, most notably, GPT(Generative Pre-training Transformer). Karpathy builds and trains entire GPT from scratch, providing a decent explanation of every step along the way. Here is a lecture video and accompanying code repository(nanoGPT).

- Stanford CS25: Transformers United V2 aims at examining how transformers work and how they are applied in different fields from NLP, CV, biology to robotics and more. This course contains excellent talks from researchers. The introductory class of recent version of the course delves into transformer architecture and it is given by Karpathy, someone who deeply understands the intricacies of neural networks.

- Formal Algorithms for Transformers provides a mathematical overview and formal algorithms of various transformer architectures.

- Transformer Taxonomy provides an excellent literature review of transformer models, architectural changes since the inception of standard transformer, post pre-training techniques and 3 training techniques.

- The Illustrated Transformer is a remarkable blog post that break the transformer model apart and explains each part intuitively.

- Transformer and attention blog series by Lilian Weng also provide excellent understanding of transformer and attention mechanism. A notable example of relevant Lilian Weng blogs are The Transformer Family Version(there is also version 2 of this blog) and Attention? Attention!.

- Attention is All You Need Video by Yannic Kilcher walkthroughs the paper, explaining all the relevant concepts and related works well.

- Transformer models: an introduction and catalog is also another resource that is worth mentioning. It provides a decent catalog of popular transformer models.

Conclusion

The significance of transformer neural network architecture can not be overstated in the field of deep learning and computer science. The transformer model, initially introduced for neural machine translation has evolved into a versatile and general-purpose architecture, demonstrating impressive performance beyond natural language processing into other various modalities.

Throughout this article, we have delved into the core mechanics of the transformer and its essential components - its encoder and decoder structure, attention mechanism, multi-head attention, MLPs, embedding, positional encoding layers, and more. We have explored several benefits of self-attention, along with potential drawbacks. Also, by examining the visualization of attention, we have gained a deeper understanding of how transformers focus on different parts of the input sequence to generate outputs.

Transformers are at the core of large language models(LLMs) which has taken the world by a storm recently. We have seen evolution of LLMs and their different design styles, and the applications of transformers beyond NLP. We have also talked their current challenges, including the need for more efficient models and the effective use of context window. These challenges present exciting opportunities for future research and improvements.

As deep learning field continues to evolve, transformer architecture remains a foundational building block of modern machine learning systems. There are many variations of transformer architectures, but regardless of what the future of transformers holds, one thing has been certain - attention is all you need. Stay curious, keep learning, and always pay attention!

References

- Akyürek, Ekin, Dale Schuurmans, Jacob Andreas, Tengyu Ma, and Denny Zhou. 2023. “What Learning Algorithm Is in-Context Learning? Investigations with Linear Models.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2211.15661.

- Alayrac, Jean-Baptiste, Jeff Donahue, Pauline Luc, Antoine Miech, Iain Barr, Yana Hasson, Karel Lenc, et al. 2022. “Flamingo: A Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2204.14198.

- Ba, Jimmy Lei, Jamie Ryan Kiros, and Geoffrey E Hinton. 2016. “Layer Normalization.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1607.06450.

- Bahdanau, Dzmitry, Kyunghyun Cho, and Yoshua Bengio. 2014. “Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1409.0473.

- Bommasani, Rishi, Drew A Hudson, Ehsan Adeli, Russ Altman, Simran Arora, Sydney von Arx, Michael S Bernstein, et al. 2022. “On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2108.07258.

- Bousmalis, Konstantinos, Giulia Vezzani, Dushyant Rao, Coline Devin, Alex X Lee, Maria Bauza, Todor Davchev, et al. 2023. “RoboCat: A Self-Improving Foundation Agent for Robotic Manipulation.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2306.11706.

- Brohan, Anthony, Noah Brown, Justice Carbajal, Yevgen Chebotar, Joseph Dabis, Chelsea Finn, Keerthana Gopalakrishnan, et al. 2022. “RT-1: Robotics Transformer for Real-World Control at Scale.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2212.06817.

- Brown, Tom B, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, et al. 2020. “Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2005.14165.

- Carion, Nicolas, Francisco Massa, Gabriel Synnaeve, Nicolas Usunier, Alexander Kirillov, and Sergey Zagoruyko. 2020. “End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2005.12872.

- Chen, Lili, Kevin Lu, Aravind Rajeswaran, Kimin Lee, Aditya Grover, Michael Laskin, Pieter Abbeel, Aravind Srinivas, and Igor Mordatch. 2021. “Decision Transformer: Reinforcement Learning via Sequence Modeling.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2106.01345.

- Chen, Shouyuan, Sherman Wong, Liangjian Chen, and Yuandong Tian. 2023. “Extending Context Window of Large Language Models via Positional Interpolation.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2306.15595.

- Chen, Xi, Josip Djolonga, Piotr Padlewski, Basil Mustafa, Soravit Changpinyo, Jialin Wu, Carlos Riquelme Ruiz, et al. 2023. “PaLI-x: On Scaling up a Multilingual Vision and Language Model.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2305.18565.

- Chollet, François. 2017. “Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1610.02357.

- Chowdhery, Aakanksha, Sharan Narang, Jacob Devlin, Bosma Maarten, Mishra Gaurav, Roberts Adam, Barham Paul, et al. 2022. “PaLM: Scaling Language Modeling with Pathways.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2204.02311.

- Chung, Hyung Won, Le Hou, Shayne Longpre, Barret Zoph, Yi Tay, William Fedus, Yunxuan Li, et al. 2022. “Scaling Instruction-Finetuned Language Models.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2210.11416.

- Dao, Tri. 2023. “FlashAttention-2: Faster Attention with Better Parallelism and Work Partitioning.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2307.08691.

- Dao, Tri, Daniel Y. Fu, Stefano Ermon, Atri Rudra, and Christopher Ré. 2022. “FlashAttention: Fast and Memory-Efficient Exact Attention with IO-Awareness.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2205.14135.

- Dehghani, Mostafa, Anurag Arnab, Lucas Beyer, Ashish Vaswani, and Yi Tay. 2022. “The Efficiency Misnomer.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2110.12894.

- Devlin, Jacob, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. “BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding.” In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), 4171–86.

- Dosovitskiy, Alexey, Lucas Beyer, Alexander Kolesnikov, Dirk Weissenborn, Xiaohua Zhai, Thomas Unterthiner, Mostafa Dehghani, et al. 2021. “An Image Is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale.” In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Girdhar, Rohit, Alaaeldin El-Nouby, Zhuang Liu, Mannat Singh, Kalyan Vasudev Alwala, Armand Joulin, and Ishan Misra. 2023. “ImageBind: One Embedding Space to Bind Them All.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2305.05665.

- Graves, Alex, Greg Wayne, and Ivo Danihelka. 2014. “Neural Turing Machines.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1410.5401.

- He, Kaiming, Xinlei Chen, Saining Xie, Yanghao Li, Piotr Dollár, and Ross Girshick. 2021. “Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2111.06377.

- He, Kaiming, Xiangyu Zhang, Shaoqing Ren, and Jian Sun. 2016. “Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition.” In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–78. Hoffmann, Jordan, Sebastian Borgeaud, Arthur Mensch, Elena Buchatskaya, Trevor Cai, Eliza Rutherford, Diego de Las Casas, et al. 2022. “Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2203.15556.

- Ioffe, Sergey, and Christian Szegedy. 2015. “Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift.” In International Conference on Machine Learning, 448–56.

- Le Scao, Teven, Angela Fan, Christopher Akiki, Pavlick Ellie, Ilić Suzana, Hesslow Daniel, Castagné Roman, et al. 2022. “BLOOM: A 176B-Parameter Open-Access Multilingual Language Model.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2211.05100.

- Lewis, Mike, Yinhan Liu, Naman Goyal, Marjan Ghazvininejad, Abdelrahman Mohamed, Omer Levy, Veselin Stoyanov, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2019. “BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-Training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1910.13461.

- Lewkowycz, Aitor, Anders Andreassen, David Dohan, Ethan Dyer, Henryk Michalewski, Vinay Ramasesh, Ambrose Slone, et al. 2022. “Solving Quantitative Reasoning Problems with Language Models.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2206.14858.

- Liu, Nelson F., Kevin Lin, John Hewitt, Ashwin Paranjape, Michele Bevilacqua, Fabio Petroni, and Percy Liang. 2023. “Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2307.03172.

- Liu, Yinhan, Myle Ott, Naman Goyal, Jingfei Du, Mandar Joshi, Danqi Chen, Omer Levy, Mike Lewis, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Veselin Stoyanov. 2019. “RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1907.11692.

- Lu, Jiasen, Christopher Clark, Rowan Zellers, Roozbeh Mottaghi, and Aniruddha Kembhavi. 2022. “Unified-IO: A Unified Model for Vision, Language, and Multi-Modal Tasks.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2206.08916.

- Luong, Minh-Thang, Hieu Pham, and Christopher D Manning. 2015. “Effective Approaches to Attention-Based Neural Machine Translation.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1508.04025.

- Mehta, Sachin, and Mohammad Rastegari. 2022. “MobileViT: Light-Weight, General-Purpose, and Mobile-Friendly Vision Transformer.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2110.02178.

- OpenAI. 2023. “GPT-4 Technical Report.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2303.08774.

- Parmar, Niki, Ashish Vaswani, Jakob Uszkoreit, Łukasz Kaiser, Noam Shazeer, Alexander Ku, and Dustin Tran. 2018. “Image Transformer.” In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, 4055–64.

- Radford, Alec, Jong Wook Kim, Chris Hallacy, Aditya Ramesh, Gabriel Goh, Sandhini Agarwal, Girish Sastry, et al. 2021. “Learning Transferable Visual Models from Natural Language Supervision.” In International Conference on Machine Learning, 8748–63.

- Radford, Alec, Jong Wook Kim, Tao Xu, Greg Brockman, Christine McLeavey, and Ilya Sutskever. 2022. “Robust Speech Recognition via Large-Scale Weak Supervision.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2212.04356.

- Radford, Alec, Karthik Narasimhan, Tim Salimans, and Ilya Sutskever. 2018. “Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training.”

- Radford, Alec, Jeffrey Wu, Rewon Child, David Luan, Dario Amodei, and Ilya Sutskever. 2019. “Language Models Are Unsupervised Multitask Learners.” OpenAI Blog 1 (8).

- Raffel, Colin, Noam Shazeer, Adam Roberts, Katherine Lee, Sharan Narang, Michael Matena, Yanqi Zhou, Wei Li, and Peter J Liu. 2019. “Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1910.10683.

- Ramesh, Aditya, Prafulla Dhariwal, Alex Nichol, Casey Chu, and Mark Chen. 2022. “Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2204.06125.

- Reed, Scott, Konrad Zolna, Emilio Parisotto, Sergio Gomez Colmenarejo, Alexander Novikov, Gabriel Barth-Maron, Mai Gimenez, et al. 2022. “A Generalist Agent.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2205.06175.

- Rombach, Robin, Andreas Blattmann, Dominik Lorenz, Patrick Esser, and Björn Ommer. 2022. “High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models.” In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 10684–95.

- Singhal, Karan, Shekoofeh Azizi, Tao Tu, S Sara Mahdavi, Jason Wei, Hyung Won Chung, Nathan Scales, et al. 2022. “Large Language Models Encode Clinical Knowledge.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2212.13138.

- Srivastava, Nitish, Geoffrey Hinton, Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Ruslan Salakhutdinov. 2014. “Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 15 (56): 1929–58.

- Steiner, Andreas, Alexander Kolesnikov, Xiaohua Zhai, Ross Wightman, Jakob Uszkoreit, and Lucas Beyer. 2021. “How to Train Your ViT? Data, Augmentation, and Regularization in Vision Transformers.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2106.10270.

- Sun, Chen, Abhinav Shrivastava, Saurabh Singh, and Abhinav Gupta. 2017. “Revisiting Unreasonable Effectiveness of Data in Deep Learning Era.” In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 843–52.

- Sun, Simeng, Kalpesh Krishna, Andrew Mattarella-Micke, and Mohit Iyyer. 2021. “Do Long-Range Language Models Actually Use Long-Range Context?” In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 807–22. Online; Punta Cana, Dominican Republic: Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2021.emnlp-main.62.

- Tay, Yi, Mostafa Dehghani, Dara Bahri, and Donald Metzler. 2020. “Efficient Transformers: A Survey.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2009.06732.

- Tay, Yi, Mostafa Dehghani, Vinh Q Tran, Xavier Garcia, Jason Wei, Xuezhi Wang, Hyung Won Chung, et al. 2022. “UL2: Unifying Language Learning Paradigms.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2205.05131.

- Taylor, Ross, Marcin Kardas, Guillem Cucurull, Thomas Scialom, Anthony Hartshorn, Elvis Saravia, Andrew Poulton, Viktor Kerkez, and Robert Stojnic. 2022. “Galactica: A Large Language Model for Science.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2211.09085.

- Touvron, Hugo, Matthieu Cord, Alaaeldin El-Nouby, Piotr Bojanowski, Armand Joulin, Gabriel Synnaeve, and Hervé Jégou. 2021. “Augmenting Convolutional Networks with Attention-Based Aggregation.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2112.13692.

- Touvron, Hugo, Thibaut Lavril, Gautier Izacard, Xavier Martinet, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Timothée Lacroix, Baptiste Rozière, et al. 2023. “LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2302.13971.

- Vaswani, Ashish, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. 2017. “Attention Is All You Need.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1706.03762.

- Vig, Jesse. 2019. “A Multiscale Visualization of Attention in the Transformer Model.” In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, 37–42.

- Wang, Guangyu, Guoxing Yang, Zongxin Du, Longjun Fan, and Xiaohu Li. 2023. “ClinicalGPT: Large Language Models Finetuned with Diverse Medical Data and Comprehensive Evaluation.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2306.09968.

- Wang, Peng, An Yang, Rui Men, Junyang Lin, Shuai Bai, Zhikang Li, Jianxin Ma, Chang Zhou, Jingren Zhou, and Hongxia Yang. 2022. “OFA: Unifying Architectures, Tasks, and Modalities Through a Simple Sequence-to-Sequence Learning Framework.” In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning, 23318–40. PMLR.

- Wang, Zirui, Jiahui Yu, Adams Wei Yu, Zihang Dai, Yulia Tsvetkov, and Yuan Cao. 2021. “SimVLM: Simple Visual Language Model Pretraining with Weak Supervision.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2108.10904.

- Wei, Jason, Max Nye, and Percy Liang. 2022. “Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2201.11903.

- Wei, Jason, Yi Tay, Rishi Bommasani, Colin Raffel, Barret Zoph, Sebastian Borgeaud, Dani Yogatama, et al. 2022. “Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2206.07682.

- Wei, Jerry, Jason Wei, Yi Tay, Dustin Tran, Albert Webson, Yifeng Lu, Xinyun Chen, et al. 2023. “Larger Language Models Do in-Context Learning Differently.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2303.03846.

- Wolf, Thomas, Lysandre Debut, Victor Sanh, Julien Chaumond, Clement Delangue, Anthony Moi, Pierric Cistac, et al. 2020. “Transformers: State-of-the-Art Natural Language Processing.” In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations, 38–45. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.emnlp-demos.6.

- Wu, Shijie, Ozan Irsoy, Steven Lu, Vadim Dabravolski, Mark Dredze, Sebastian Gehrmann, Prabhanjan Kambadur, David Rosenberg, and Gideon Mann. 2023. “BloombergGPT: A Large Language Model for Finance.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2303.17564.

- Xie, Shufang, Huishuai Zhang, Junliang Guo, Xu Tan, Jiang Bian, Hany Hassan Awadalla, Arul Menezes, Tao Qin, and Rui Yan. 2023. “ResiDual: Transformer with Dual Residual Connections.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2304.14802.

- Xiong, Ruibin, Yunchang Yang, Di He, Kai Zheng, Shuxin Zheng, Chen Xing, Huishuai Zhang, Yanyan Lan, Liwei Wang, and Tie-Yan Liu. 2020. “On Layer Normalization in the Transformer Architecture.” In International Conference on Machine Learning, 10524–33.

- Xu, Kelvin, Jimmy Ba, Ryan Kiros, Kyunghyun Cho, Aaron Courville, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Richard S Zemel, and Yoshua Bengio. 2015. “Show, Attend and Tell: Neural Image Caption Generation with Visual Attention.” In International Conference on Machine Learning, 2048–57.

- Xue, Linting, Noah Constant, Adam Roberts, Mihir Kale, Rami Al-Rfou, Aditya Siddhant, Aditya Barua, and Colin Raffel. 2021. “mT5: A Massively Multilingual Pre-Trained Text-to-Text Transformer.” In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 483–98.

- Yang, Hongyang, Xiao-Yang Liu, and Christina Dan Wang. 2023. “FinGPT: Open-Source Financial Large Language Models.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2306.06031.

- Yang, Jingfeng, Hongye Jin, Ruixiang Tang, Xiaotian Han, Qizhang Feng, Haoming Jiang, Bing Yin, and Xia Hu. 2023. “Harnessing the Power of LLMs in Practice: A Survey on ChatGPT and Beyond.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2304.13712.

- Zhang, Xiang, and Yann LeCun. 2015. “Text Understanding from Scratch.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1502.01710.

- Zhang, Yiyuan, Kaixiong Gong, Kaipeng Zhang, Hongsheng Li, Yu Qiao, Wanli Ouyang, and Xiangyu Yue. 2023. “Meta-Transformer: A Unified Framework for Multimodal Learning.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:2307.10802.

Footnotes

Example adapted from Deep Learning with Python by Francois Cholle. ↩︎

In the transformer paper, MLPs are what referred to as feed-forward networks(FFNs). I find the terminology of FFNs confusing sometime. MLPs are feed-forward networks but not the other way around. ↩︎